Unlocking the Potential: Can CNC Machines Truly Handle 3D Printing?

For manufacturers, hobbyists, and engineers exploring digital fabrication, a persistent question often arises: Can my CNC machine also function as a 3D printer? This seemingly simple query taps into deeper concerns about resource utilization, investment efficiency, and the fundamental capabilities of these powerful tools. This guide cuts through common misconceptions, exploring the technical realities and practical trade-offs of using CNC machinery for additive manufacturing. We’ll answer your burning questions about feasibility, limitations, cost-effectiveness, setup complexity, and where dedicated solutions shine.

Section 1: Understanding Fundamentals – CNC vs. 3D Printing Tech

Clarifying the core differences lays the groundwork for understanding the challenges and possibilities.

Q1: What’s the fundamental difference between CNC machining and 3D printing?

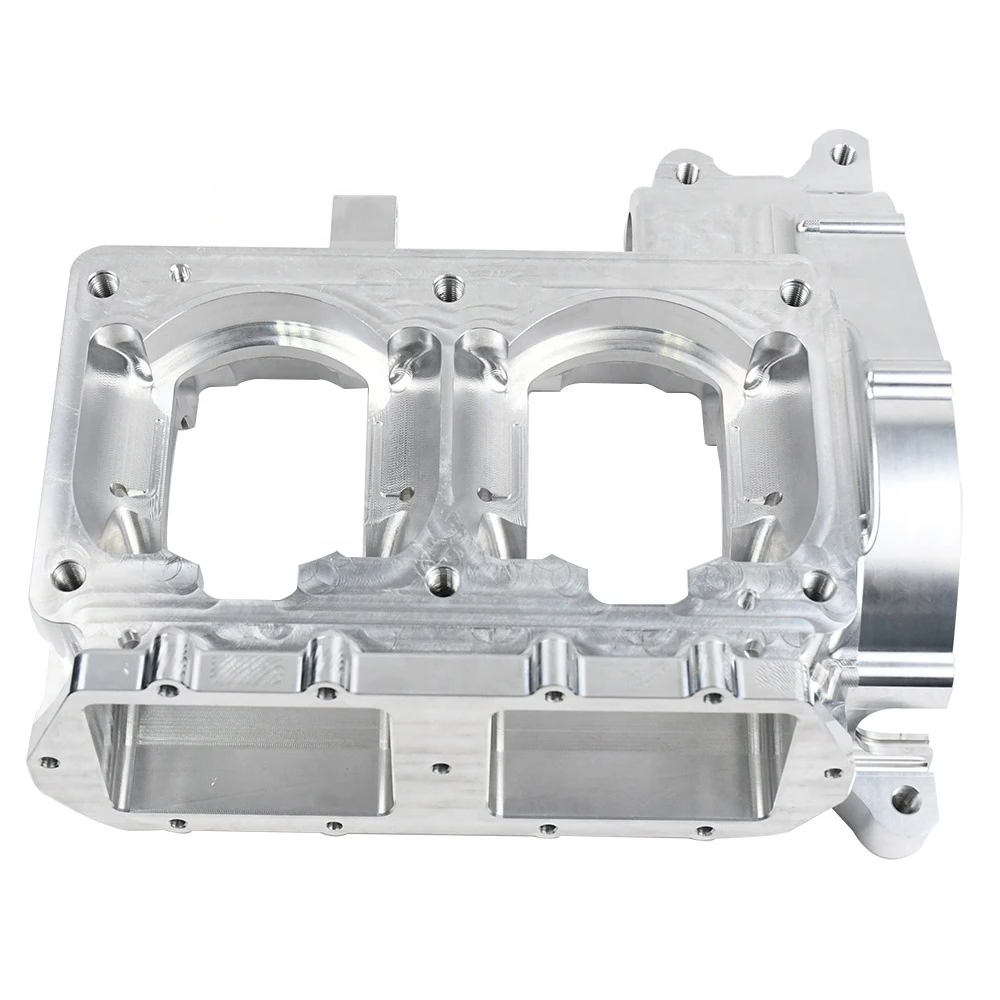

- A1. Core Answer: CNC machining is a subtractive manufacturing process (removing material to shape a part), while most 3D printing is an additive manufacturing process (building parts by adding material layer-by-layer). These core principles dictate their distinct hardware setups.

- A2. In-depth Explanation and Principles: CNC machines (like mills, routers) precisely remove material from a solid block (workpiece) using rotating cutting tools guided by programmed paths (G-code). Material removal (subtraction) produces chips/swarf. 3D printers, conversely, melt/extrude filament (FDM/FFF), sinter powder (SLS), cure resin (SLA/DLP), or deposit bonding agents (Jetting/Binder Jetting) to create objects by adding matter incrementally. The physics of deposition, adhesion, support generation, and thermal control differ fundamentally from high-force cutting.

- A3. Action Guide and Recommendations: Identify your primary need: If you consistently produce parts requiring high precision from metal or dense plastics by removing material, CNC is essential. For rapidly prototyping complex geometries with plastic/composite polymers or producing polymer/low-temp metal end-use parts requiring minimal post-processing, dedicated 3D printing excels. A ‘Comparison Guide: CNC vs. 3D Printing’ can be inserted here for deeper analysis.

Q2: Are CNC and 3D printers controlled similarly?

- A1. Core Answer: While both typically rely on computer numeric control (CNC) interpreting CAD/CAM instructions (like G-code) to move toolheads precisely, the axes controlled and the actions executed at the toolhead differ dramatically.

- A2. In-depth Explanation and Principles: Both use servo/stepper motors actuating Cartesian (X/Y/Z) axes. However, a CNC mill controls spindle speed (RPM), tool changes, coolant flow, and forceful Z-axis plunging. A typical FDM 3D printer controls extruder temperature, filament feed rate, layer cooling fans, and potentially a heated bed temperature, focusing on precise material deposition rates, not high cutting forces. The G-code commands ("G1 move", "M3 spindle on") overlap, but the M-codes specific to temperature control or material extrusion differ significantly.

- A3. Action Guide and Recommendations: Check your CNC controller: Older controllers lack the firmware hooks/extensibility for critical AM features like thermal management. Research retrofitting solutions like ‘Mach4 with AM plugins’ or Arduino/GRBL-based add-ons if basic axis motion compatibility exists. (Visual: "Components Comparison Diagram" highlighting control differences can be inserted here).

Q3: Why isn’t my CNC router already able to 3D print?

- A1. Core Answer: Primarily because lacks critical hardware (thermally controlled extruder or printhead) and specialized software/firmware needed to handle material deposition instead of removal.

- A2. In-depth Explanation and Principles: CNC routers/mills are engineered for rigidity and torque to withstand cutting forces. Their spindles rotate cutting tools at high speeds; they don’t incorporate material feeders, heaters, nozzles, or thermal sensors. Firmware isn’t programmed to interpret commands specific to extruding filament or solidifying powder/resin. Implementing these features requires significant modification.

- A3. Action Guide and Recommendations: Inventory your CNC: Does it have spare control outputs? Space to mount auxiliary motors/systems? Can you reconfigure the spindle mount? If yes, explore retrofit kits. Otherwise, acknowledge substantial hardware adaptation needed. Your machine control may support it, but critical deposition hardware is missing (Refer to our ‘CNC Machine Upgrade Checklist’).

Section 2: Possibilities and Limitations of CNC Retrofitting

Exploring if and how an existing CNC machine can be adapted for additive work.

Q4: Can I retrofit my existing CNC mill to become a 3D printer?

- A1. Core Answer: Technically possible, especially for Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF/FDM), but often complex, compromises capability, and requires significant effort/resources. Success depends heavily on machine specifics and expertise.

- A2. In-depth Explanation and Principles: Retrofitting involves replacing the spindle with a filament extruder assembly (hotend, cold end feeder, heater block), adding a heated build platform, integrating temperature controls/sensors into the CNC control loop, and using slicing software capable of generating suitable toolpaths/G-code for deposition. Key challenges: CNC bed/platform is often not designed for leveling/tramming precise to fractions of a millimeter (~0.1mm) crucial for layer adhesion in AM. Rigidity optimized for cutting might hinder rapid direction changes needed for printing contours. Enclosures may not be suitable for maintaining ambient temperature. Software compatibility hurdles are frequent.

- A3. Action Guide and Recommendations:

- Assess Feasibility: Can you remove the spindle? Is there mounting space/power for extruder motors/hotend? Can controller handle extra thermal PID loops?

- Research Kits: Look for vendor-specific CNC-to-FDM conversion kits.

- Specialized Slicer: Use slicers designed for CNC-based FDM conversion (e.g., extended GRBL slicers).

- Calibration Focus: Expect to spend substantial time calibrating extrusion rates, nozzle height (Z-offset), and bed leveling. (Visual: "CNC Retrofit Diagram" illustrating components can be inserted here).

Q5: What are the major limitations of using a retrograded CNC for 3D printing?

- A1. Core Answer: Print quality, material options, print volume utilization, speed, and reliability will typically fall short compared to dedicated 3D printers, requiring compromises and constant attention.

- A2. In-depth Explanation and Principles: Common compromises include:

- Bed Leveling: CNC beds often lack truly planar surfaces or easy leveling mechanisms vital for first-layer adhesion in FDM.

- Frame Rigidity vs. Agility: Optimizing milling stability can make frames overdamped/too massive for rapid deposition direction changes, limiting print speed & introducing vibration artifacts.

- Thermal Management: Adequately heating a large metal bed consumes significant power; enclosures may trap dust/shavings harmful to printed parts. Cooling systems optimized for milling may overwhelm printed layers.

- Material Versatility: FDM filament printing dominates retrofits; handling advanced materials (flexibles, composites, high-temp) or switching techs (SLA, SLS) is impractical.

- Accuracy/Resolution: Achieving fine surface finishes common in resin printing is impossible; FDM resolution depends heavily on nozzle size and calibration.

- A3. Action Guide and Recommendations: Set realistic expectations: Retrofit prints will likely be functional prototypes or rough forms, not high-resolution cosmetic parts. Prioritize understanding Understanding PID Tuning]. Monitor prints closely. Dedicate the machine: Frequently switching between milling duties and printing setups is cumbersome and recalibration-heavy.

Q6: Are CNC routers easier to convert for printing than mills?

- A1. Core Answer: **Potentially yes, especially gantry-style routers, due to generally lighter structures and