In 2022, in San Antonio, Texas, Dr. Arturo Bonilla implanted an external ear in a 20-year-old woman born without ears. The woman’s right ear is custom made to fit the size and shape of her left side. Bonilla is a pediatric orthopedic surgeon with over 25 years of experience treating congenital ear defects and is a recognized expert in the field. Unlike previous surgeries, the ear implants used in this surgery were 3D bioprinted using the woman’s own cartilage cells.

From the germ of an idea to actual science, 3D bioprinting is making advancements in all aspects of medical research, not only in research but also over time. Although the pace is still slow and decades remain before reaching the goals of some of the most ambitious 3D projects, progress is real. Tal Dvir, director of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine at Tel Aviv University in Israel, said: “I think within 10 years we will have transplantable organs, starting with simple organs like skin and cartilage, then moving on to more complex tissues, and finally heart, liver, kidney.

The future of 3D bioprinting

It sounds dreamy, but it’s already happening. Multiple layers of skin, bones, muscle structures, blood vessels, retinal tissue and even miniature organs have been 3D printed. Although no printed products have yet been approved for human use, the studies remain mind-blowing. Bonilla’s ear surgery mentioned above is the first 3D bioprinting to implant living cells into the human body, which is a significant milestone.

Polish researchers bioprinted a working prototype of the pancreas, and two weeks after observation, the pigs had stable blood flow. United Therapeutics Corporation has 3D printed a human lung scaffold with 4,000 km of capillaries and 200 million alveoli (tiny air sacs) capable of exchanging oxygen in animal models, marking the first step toward creating a tolerable and transplantable lung. A crucial step forward for human lungs.

At Wake Forest University’s Institute for Regenerative Medicine, scientists have developed a mobile skin bioprinting system. In the near future, they hope to be able to use the printer directly on patients with unhealed wounds, such as burns, by scanning and measuring the wound area and 3D printing the skin, layer by layer, to create it and apply it directly to the wound. The researchers also took a closer look at the 3D printed skeletal muscle structure, demonstrating that it can contract in rodents and restore more than 80% of previously lost muscle function in the front leg muscles within eight weeks.

Dvir’s own lab has created a 3D-printed “rabbit-sized” heart that contains cells, cavities, major blood vessels and a heartbeat. The professor points out that an intact human heart requires the same basic technology, although the enlargement process is very complex.

How 3D bioprinting works

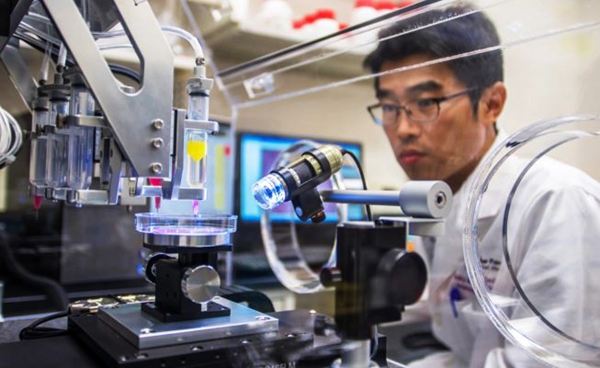

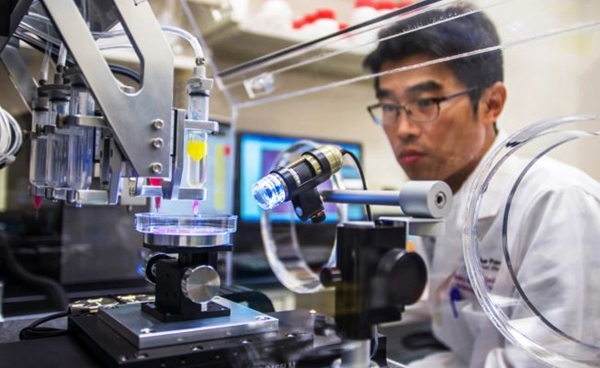

△ Multiple layers of skin, bones, muscle structures, blood vessels, retinal tissue and even miniature organs have been 3D printed, but none have yet been approved for human use.

3D printing of human organs is a shocking concept. Nearly 106,000 Americans are currently on the waiting list for organ donation, and 17 people die every day while waiting, according to the federal Health Resources and Services Administration. A 3D printing process that uses a patient’s own cells to grow organs could not only reduce waiting lists, but also significantly reduce the risk of organ rejection and potentially eliminate the need for harmful lifelong immunosuppressive drugs .

“The ability to place different types of cells in precise locations to build complex tissues, as well as the ability to integrate blood vessels that provide the oxygen and nutrients needed to keep cells alive, will be useful,” he said. said Mark Skylar-Scott, assistant professor. at Stanford’s Department of Bioengineering, these two (3D) technologies are revolutionizing tissue engineering, a field that has grown very rapidly over the past two decades, from printed bladders to now highly cellular tissues with blood vessels that can be connected to pumps and products. similar to those with a complex 3D model of cardiac components incorporating cardiac cells.

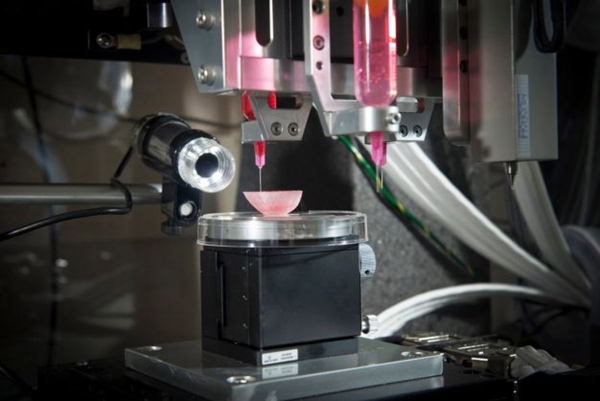

In 3D bioprinting, the materials used are cells. The process first generates the cells that researchers want to bioprint, then turns those cells into printable living inks, or bioinks, which involves mixing them with materials like gelatin or alginate to give them a consistency similar to that of toothpaste. The Stanford lab is studying how stem cells can form this consistency naturally if they are packed together at high density. If this problem is solved, 3D printed organs could be made entirely from a patient’s own cells.

The actual 3D bioprinting process involves loading bioink into a syringe and then extracting it from a nozzle. It usually involves placing different types of cells, each loaded into a different nozzle. Once completed, the tissue is connected to a pump that circulates oxygen and nutrients through it, and over time the tissue grows on its own and increases in maturity and function. “As with any research, there will likely be iterations in future patients to try to improve this technology, and we don’t know when this will become a primary treatment, but the future is very exciting,” Bonilla said.

Benefits of 3D printing

△3D bioprinting allows scientists to design tissues more precisely.

Scientists at Wake Forest University have been growing organs and tissues in the laboratory for years. They used 3D printing to create a mini-kidney and mini-liver in the lab. The next challenge: larger, more robust structures that better simulate organ function. “We’re a long way from getting there at the organ level,” said Jennifer Lewis, Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University.

“We have been able to print flat structures like skin, tubular structures like blood vessels, or non-tubular hollow organs like bladders,” said Anthony Atala, founding director of the Wake Forest Institute. “Larger solid organs are different. The blood supply and nutrients needed are different. “Scientists have successfully created heart cells from stem cells, but they don’t beat as hard as human heart cells. the same goes for liver cells (metabolism) and kidney cells (filtrate absorption). In a way, the field of 3D bioprinting awaits a major breakthrough from fundamentalist biologists.

Most researchers believe that large-scale 3D printed human organ transplants could be possible within 20 to 30 years. Dvir said: “Looking to the future, humans will not need donor hearts or livers. That’s my opinion. I’m optimistic about 3D printing organs. It’s the development trend of science.”

Source: Antarctic Bear

Daguang focuses on providing solutions such as precision CNC machining services (3-axis, 4-axis, 5-axis machining), CNC milling, 3D printing and rapid prototyping services.