In the intricate world of precision manufacturing, where tolerances are measured in microns and the geometry of a part can define its entire function, two fundamental directional terms form the bedrock of engineering communication and machining strategy: radial and axial. For engineers, designers, and procurement specialists sourcing custom precision parts, a clear and practical understanding of these terms is not just academic—it’s essential for ensuring designs are manufacturable, specifications are clear, and the final component performs flawlessly in its application. This deep dive will demystify these concepts, explore their critical role in CNC machining, and illustrate how partnering with a manufacturer that masters both dimensions is key to project success.

H2: The Core Definitions: Axial vs. Radial

At its simplest, these terms describe direction relative to a central axis of rotation or symmetry, most commonly that of a workpiece on a lathe or a spindle on a milling machine.

Axial refers to directions along or parallel to the central axis. Think of it as the direction in which the axis points. Movement or measurement along this line is axial.

Analogy: The direction a bolt is driven into a nut (in and out) is axial.

In Machining: On a lathe, the tool moving along the length of the rotating workpiece (from headstock to tailstock) is moving in the axial direction. The “runout” of a spindle along its centerline is axial runout.

Radial refers to directions perpendicular to or radiating out from the central axis. Think of it as moving outward from the center like a radius.

Analogy: The spokes on a bicycle wheel extend in radial directions from the hub.

In Machining: On a lathe, the tool moving directly toward or away from the centerline of the rotating workpiece is moving in the radial direction. The “wobble” of a spindle is radial runout.

Visualizing the Difference: Imagine a simple cylindrical shaft. Its length is measured in the axial direction. Its diameter is measured in the radial direction. Any feature like a groove around its circumference is machined via radial tool movement, while a groove along its length is machined via axial tool movement.

H2: Why This Distinction is Critical in CNC Machining

Understanding axial and radial isn’t just about vocabulary; it directly impacts design, machining strategy, quality control, and part performance.

H3: 1. Design for Manufacturability (DFM)

A designer must consider how features will be machined. A deep, small-diameter hole (axial feature) may require specialized drills and pecking cycles, while a thin, large-diameter flange (radial feature) may be prone to vibration during milling, requiring careful fixturing and toolpath planning. Clearly specifying dimensions and tolerances in axial and radial terms eliminates ambiguity on the technical drawing.

H3: 2. Machining Strategy and Toolpath Generation

CNC programmers live in a world of axes (X, Y, Z). For turning operations:

The Z-axis is typically aligned with the axial direction of the spindle.

The X-axis controls radial movement.

For 5-axis milling, the interplay becomes more complex, as the tool can approach a part from multiple angles, but the concepts of applying force or measuring relative to a local feature’s axis remain paramount. Efficient toolpaths minimize unnecessary axial and radial engagement that can cause tool deflection or poor surface finish.

H3: 3. Tolerancing and Metrology

This is where the distinction becomes non-negotiable. Tolerances are often specified differently for axial vs. radial dimensions.

Axial Tolerances: Might govern the critical spacing between bearing seats on a shaft or the depth of a sealing groove.

Radial Tolerances: Are crucial for fit and function, such as the diameter of a piston (radial dimension) that must mate with a cylinder bore with a precise clearance.

Runout: This is a composite tolerance that specifically controls the combined variation of radial and axial displacement of a surface during rotation. It is a direct measure of how much a part “wobbles” (radially) and “moves in and out” (axially) when spun.

H3: 4. Part Function and Performance

The forces a part withstands in service align with these directions.

Axial Loads: Forces applied along the axis, such as thrust in a bearing or tension in a bolt.

Radial Loads: Forces applied perpendicular to the axis, such as the weight on a shaft or pressure on a cylinder wall.

The part’s geometry, material grain structure (influenced by machining), and residual stresses must be suitable for its primary load direction.

H2: The Manufacturing Partner’s Role: Mastering Both Dimensions

The ability to consistently and precisely control both axial and radial dimensions separates a competent machine shop from a world-class precision partner. This mastery hinges on several pillars:

H3: 1. Advanced Equipment with Inherent Accuracy

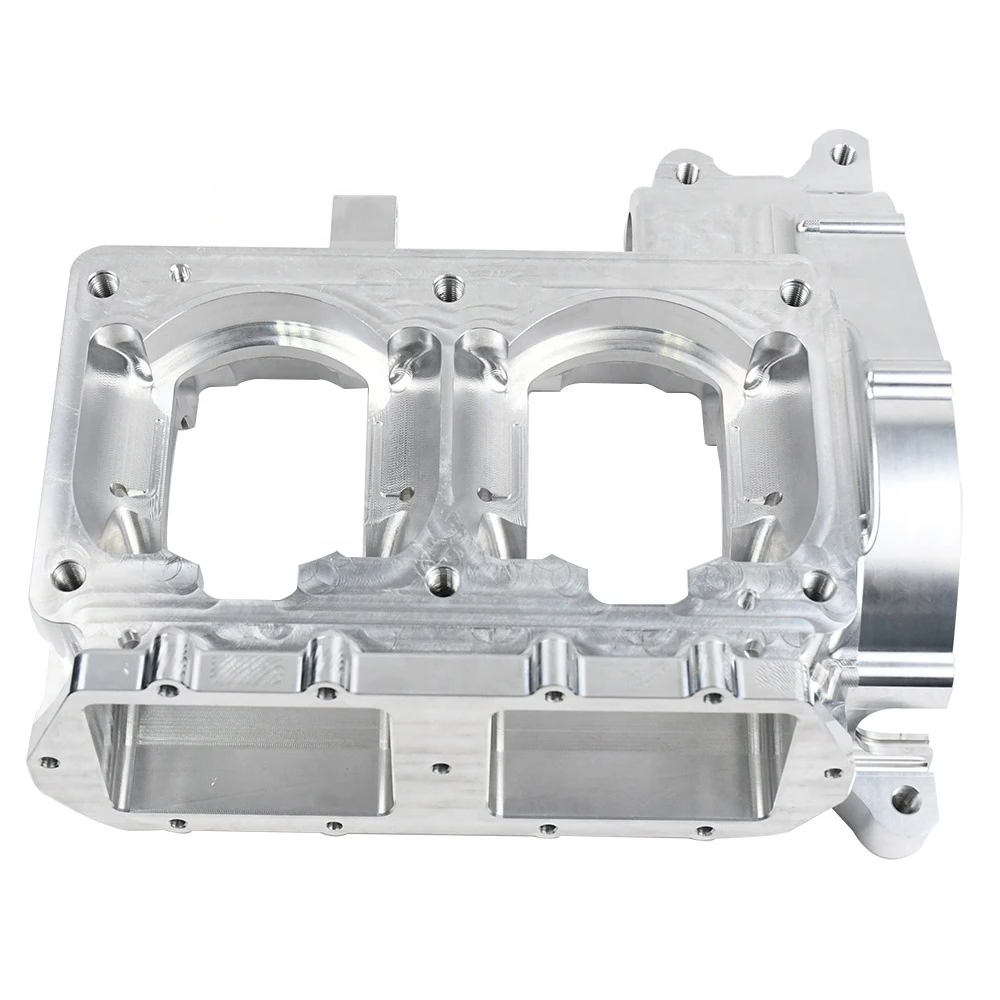

High-precision machining begins with stable, rigid machines with minimal thermal growth and exceptional geometric accuracy. For instance, a precision 5-axis CNC machining center from a manufacturer like GreatLight CNC Machining Factory isn’t just about complex angles; its construction ensures that movements along every axis (and thus every radial and axial path it generates) are predictable and repeatable within micron-level tolerances. Similarly, their turning centers and mill-turn machines are designed to minimize axial and radial runout at the spindle, which is the foundation for machining accurate parts.

H3: 2. Engineering Expertise and Process Design

Experienced manufacturing engineers translate design intent into a robust process. They determine:

The optimal sequence of operations to maintain datum structures.

The appropriate fixturing to support the part against cutting forces in both radial and axial directions without distortion.

The correct cutting tools, speeds, and feeds to achieve the desired surface integrity and dimensional stability in all orientations.

H3: 3. Comprehensive Metrology and Quality Assurance

Verifying conformance to axial and radial tolerances requires sophisticated measurement. A partner like GreatLight Metal employs coordinate measuring machines (CMMs), roundness testers, and laser scanners that can precisely measure features in 3D space, directly checking axial distances, radial diameters, concentricity, and total runout. This data-driven approach closes the loop, ensuring the virtual model and the physical part are in perfect agreement.

H2: Conclusion: From Concept to Precise Reality

In summary, radial and axial are the fundamental directional languages of rotational mechanics and precision machining. Grasping their meaning empowers clearer design communication, more accurate specification, and a deeper appreciation for the manufacturing process. Ultimately, the successful translation of a design featuring critical axial and radial dimensions into a high-performance component depends on choosing a manufacturing partner with the technical depth to control both dimensions with unwavering consistency. It is this holistic command over the entire spatial domain of a part that enables the creation of reliable, innovative hardware for demanding fields such as aerospace, medical devices, and automotive engineering.

H2: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: On a CNC lathe, which axis controls axial movement and which controls radial?

A: On a standard CNC lathe, the Z-axis controls movement parallel to the spindle centerline, which is the axial direction (e.g., along the length of the part). The X-axis controls movement perpendicular to the spindle centerline, which is the radial direction (e.g., controlling the diameter).

Q2: Is a hole’s depth an axial or radial dimension?

A: A hole’s depth is an axial dimension. It is measured along the axis of the hole itself. The hole’s diameter is a radial dimension relative to its own axis.

Q3: How does runout relate to axial and radial error?

A: Runout is a comprehensive tolerance that specifies the total permissible variation when a part is rotated. It includes both radial runout (the “wobble” or side-to-side movement) and axial runout (the “face wobble” or in-and-out movement). It is the combined effect of deviations in both directions.

Q4: Why might achieving a tight radial tolerance be more challenging than an axial tolerance on a thin-walled part?

A: During machining, cutting forces often have a significant component in the radial direction (pushing against the wall). For thin-walled features, this can cause deflection, vibration, or “chatter,” leading to difficulty in holding a precise diameter (radial dimension) and achieving a good surface finish. Axial dimensions on such a part might be less susceptible to this type of dynamic deflection.

Q5: What should I look for in a supplier to ensure they can meet critical axial and radial tolerances?

A: Seek evidence of:

Equipment Capability: High-precision, well-maintained CNC machines (like 5-axis or precision lathes) with low inherent runout.

Metrology Investment: Availability of advanced measuring equipment (CMM, roundness testers) to verify these tolerances.

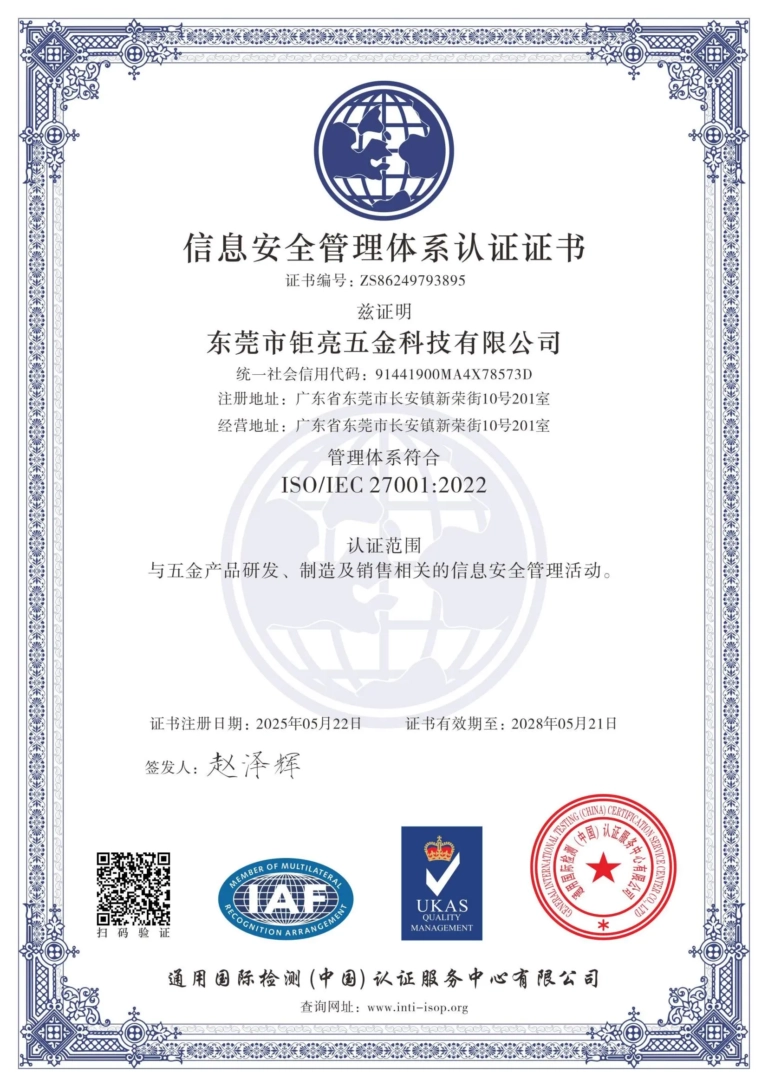

Certifications & Process Control: Adherence to quality standards like IATF 16949 for automotive or ISO 13485 for medical, which mandate rigorous process validation and control.

Technical Dialogue: Their engineers should proactively discuss fixturing, machining strategy, and potential challenges related to your part’s geometry and tolerance requirements. A partner like GreatLight CNC Machining Factory, which integrates these elements into a full-process solution, is structured to deliver on these complex requirements.