The Definitive Guide to the Four Foundational Heat Treatment Processes: Annealing, Normalizing, Quenching, and Tempering

Executive Summary: Mastering the Essential Heat Treatment Process

The heat treatment process represents one of the most critical and transformative disciplines in materials engineering and manufacturing. By applying precisely controlled heating and cooling cycles, engineers can fundamentally alter the internal microstructure of metals—primarily steels—to achieve a vast spectrum of mechanical properties. At the core of this science are four foundational techniques, often poetically termed the “Four Fires” of metallurgy: annealing, normalizing, quenching, and tempering. This comprehensive guide delves into each of these essential heat treatment process methods, providing an in-depth exploration of their scientific principles, procedural steps, intended outcomes, and industrial applications. Whether you aim to soften metal for machining, achieve supreme hardness for wear resistance, or develop an optimal balance of strength and toughness, a thorough understanding of these four processes is indispensable. This article serves as an authoritative resource for students, machinists, engineers, and manufacturing professionals seeking to master the heat treatment process to solve real-world material performance challenges, enhance product durability, and innovate in component design.

Part 1: Introduction to Heat Treatment Fundamentals

1.1 What is a Heat Treatment Process and Why is it Crucial?

A heat treatment process is a series of controlled thermal operations applied to a solid metal or alloy to obtain desired microstructural characteristics and, consequently, specific mechanical or physical properties. Unlike chemical treatments or coatings, heat treatment alters the material’s properties throughout its entire volume. The profound importance of the heat treatment process lies in its ability to make a single metal alloy serve multiple, often contradictory, functions. For instance, the same grade of medium-carbon steel can be softened for intricate machining via annealing and later hardened to form a durable gear tooth via quenching and tempering. This versatility makes the heat treatment process a cornerstone of industries ranging from automotive and aerospace to tooling and construction. It solves core user problems by enabling: extended component service life through enhanced wear resistance, prevention of in-service failures via improved toughness, reduction of manufacturing costs by improving machinability, and allowing for lightweight design through the use of higher-strength materials.

1.2 The Metallurgical Science Behind the Heat Treatment Process

The effectiveness of any heat treatment process is rooted in the principles of physical metallurgy, specifically the concept of solid-phase transformations. For ferrous metals (steels), these transformations are best understood through the iron-carbon phase diagram.

- Key Microstructural Phases: The properties of steel are dictated by the presence and arrangement of different phases:

- Ferrite: A soft, ductile, body-centered cubic (BCC) phase of iron with low carbon solubility.

- Austenite: A softer, face-centered cubic (FCC) phase stable at high temperatures, capable of dissolving significantly more carbon.

- Cementite (Fe₃C): A very hard, brittle intermetallic compound of iron and carbon.

- Pearlite: A lamellar microstructure consisting of alternating layers of ferrite and cementite, offering a good balance of strength and ductility.

- Martensite: A supersaturated, body-centered tetragonal (BCT) phase formed by the rapid quenching of austenite. It is extremely hard but brittle.

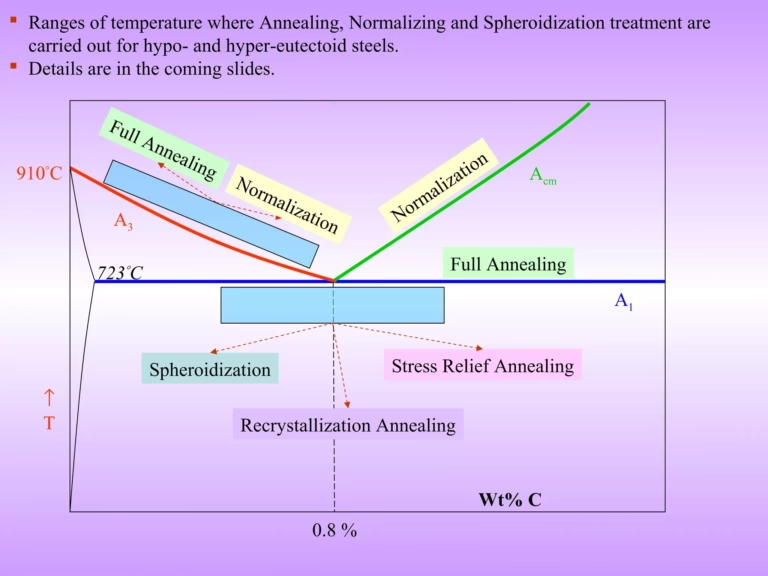

- The Role of the Phase Diagram: The iron-carbon equilibrium diagram is the fundamental roadmap for the heat treatment process. It defines the critical temperatures (such as Ac1, Ac3, and Acm) where phase transformations begin and end during heating and cooling. Every heat treatment process involves heating the steel into the austenitic region to form a homogeneous solid solution and then controlling the cooling path to transform this austenite into the desired mixture of phases (e.g., ferrite-pearlite, bainite, or martensite).

- Transformation Kinetics: While the phase diagram shows equilibrium states, most practical heat treatment process operations involve non-equilibrium cooling. Time-Temperature-Transformation (TTT) and Continuous Cooling Transformation (CCT) diagrams are used to predict the microstructural outcomes of specific cooling rates, which is the essence of processes like quenching versus annealing.

Part 2: In-Depth Analysis of Annealing

2.1 The Core Principles and Objectives of the Annealing Heat Treatment Process

Annealing is a heat treatment process characterized by heating a metal to a predetermined temperature, holding it at that temperature for a sufficient duration (soaking), and then cooling it at a very slow, controlled rate, typically inside the furnace itself (furnace cooling). The overarching goal of the annealing heat treatment process is to produce a soft, ductile, and stress-free condition by promoting a microstructure that is as close to equilibrium as possible.

The primary objectives of an annealing heat treatment process are:

- To Reduce Hardness and Increase Ductility: This is the most common reason for annealing. By producing a soft, coarse pearlitic or spheroidized structure, annealing dramatically improves a material’s machinability, allowing for easier cutting, drilling, and shaping with reduced tool wear.

- To Relieve Internal Stresses: Manufacturing processes like casting, forging, welding, and machining introduce significant residual stresses into components. The slow, uniform cooling of annealing allows these locked-in stresses to dissipate, thereby minimizing the risk of distortion, dimensional instability, or stress-corrosion cracking during storage or service.

- To Refine and Homogenize Grain Structure: Annealing can recrystallize cold-worked metals, replacing elongated, strained grains with new, strain-free equiaxed grains. It also helps to homogenize chemical segregation in castings or welds, creating a more uniform microstructure throughout the part.

- To Prepare the Microstructure for Subsequent Hardening: For high-carbon and alloy steels, a specific type of annealing (spheroidize annealing) creates an ideal starting microstructure of spherical carbides in a ferritic matrix. This structure is soft and machinable but will transform uniformly and predictably during a subsequent quenching heat treatment process.

2.2 Types and Procedures of the Annealing Heat Treatment Process

The generic term “annealing” encompasses several specific sub-processes, each tailored for a particular purpose and material type.

- Full Annealing:

- Procedure: Hypoeutectoid steels are heated to approximately 30-50°C above the Ac3 line (fully into the austenite region), soaked to achieve homogeneity, and then furnace-cooled very slowly. Hypereutectoid steels are typically heated just above the Ac1 line.

- Outcome: This produces the softest possible state with a coarse pearlitic structure (for eutectoid steels) or ferrite plus pearlite (for hypoeutectoid steels). It is ideal for achieving maximum softness and ductility.

- Industrial Application: Commonly applied to forgings, castings, and rolled stock that will undergo significant machining.

- Spheroidize Annealing:

- Procedure: Primarily for high-carbon (>0.6% C) and tool steels. The steel is heated to just below the Ac1 line (typically 700-750°C) and held for an extended period—often 15+ hours—or cycled repeatedly above and below Ac1.

- Outcome: The lamellar cementite in pearlite transforms into small, spherical carbide particles dispersed in a ferrite matrix. This structure is soft and highly machinable while providing an excellent starting point for uniform hardening.

- Industrial Application: Essential for bearing steels, tool steels, and high-carbon wire before drawing or machining.

- Process Annealing (or Intermediate Annealing):

- Procedure: Used on low-carbon steels that have been cold-worked (e.g., cold-rolled sheet, drawn wire). The material is heated to a temperature below the Ac1 line, typically between 550°C and 650°C, and then air-cooled.

- Outcome: It relieves the stresses and strain hardening from cold work, restoring ductility for further forming operations without significantly changing the grain structure or causing excessive scaling.

- Industrial Application: A standard process in multi-stage wire drawing and sheet metal forming operations.

- Stress Relief Annealing:

- Procedure: The component is heated to a temperature below the Ac1 line, usually between 500°C and 600°C, soaked, and then slowly cooled. No phase transformation occurs.

- Outcome: Its sole purpose is to reduce residual stresses by allowing atomic-level creep and relaxation. Hardness and strength are largely unaffected.

- Industrial Application: Critical for welded structures, large castings, and precision machined components to ensure dimensional stability.

2.3 Advantages, Limitations, and Best Practices for Annealing

- Advantages:

- Achieves maximum softness and ductility.

- Effectively eliminates internal stresses.

- Improves machinability and formability.

- Produces a uniform, stable microstructure.

- Limitations:

- It is a time-consuming and energy-intensive heat treatment process due to the long furnace cycle (heating, soaking, and very slow cooling).

- May result in excessive scaling (oxidation) or decarburization if not performed in a protective atmosphere.

- Produces the lowest strength and hardness condition of the major heat treatments.

- Best Practices:

- Always consider the specific material grade and its critical transformation temperatures from reference tables.

- Use protective atmospheres (e.g., nitrogen, endothermic gas) for high-value parts to prevent surface degradation.

- For large loads, ensure proper racking to allow uniform heating and cooling, preventing warping.

- Consider normalizing as a faster, more economical alternative if the required properties allow.

Part 3: Comprehensive Guide to Normalizing

3.1 Defining the Normalizing Heat Treatment Process

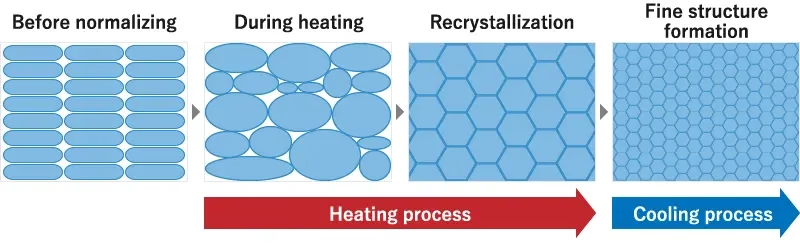

Normalizing is a heat treatment process that involves heating a ferrous alloy to a temperature significantly above its upper critical transformation range (typically 40-50°C above Ac3 or Acm), holding it until fully austenitized, and then cooling it in still or slightly agitated air at room temperature. The key differentiating factor between normalizing and annealing within the heat treatment process family is this faster cooling rate from the austenitizing temperature.

The primary intent of the normalizing heat treatment process is to refine the grain structure. The air cooling rate is fast enough to undercool the austenite more than in annealing, resulting in a higher nucleation rate for the transformation products. This yields a finer pearlitic structure (in eutectoid steels) or a finer distribution of ferrite and pearlite (in hypoeutectoid steels) compared to the coarser structures from furnace cooling.

3.2 Objectives and Metallurgical Outcomes of Normalizing

The normalizing heat treatment process serves several key objectives that make it a versatile and widely used procedure:

- Grain Refinement: It is highly effective in refining the coarse, uneven grain structures resulting from prior manufacturing processes like forging, casting, or hot rolling. A fine, uniform grain size improves both strength and toughness according to the Hall-Petch relationship.

- Homogenization of Microstructure: It promotes a more chemically and structurally homogeneous condition throughout the part, which is crucial for consistent performance.

- Modification of Carbide Structure: In hypereutectoid steels (high-carbon steels), normalizing can break up continuous, brittle networks of cementite that form at prior austenite grain boundaries, improving machinability and subsequent heat treatment response.

- Achieving a Consistent, Predictable Starting Condition: For many low and medium-carbon steels, normalizing provides a uniform, fine-grained ferrite-pearlite structure that is ideal for final use or as a preparatory step before case hardening or induction hardening.

The resultant microstructure from a normalizing heat treatment process offers a superior combination of strength, hardness, and toughness compared to an annealed state, though with slightly lower ductility and machinability.

3.3 Normalizing vs. Annealing: A Critical Comparison

Choosing between normalizing and annealing is a fundamental decision in process planning. The following table outlines the key distinctions:

| Aspect | Normalizing Heat Treatment Process | Annealing Heat Treatment Process |

|---|---|---|

| Heating Temperature | ~40-50°C above Ac3/Acm (higher than annealing). | To Ac3 + 30-50°C (Full Anneal) or below Ac1 (Process/Stress Relief). |

| Cooling Medium/Method | Still air at room temperature. | Controlled slow cooling inside the furnace. |

| Cooling Rate | Relatively faster. | Very slow. |

| Microstructure | Finer pearlite (eutectoid) or finer ferrite+pearlite. | Coarser pearlite or spheroidized carbides. |

| Mechanical Properties | Higher strength, hardness, and toughness than annealed state. | Lower strength and hardness; maximum ductility and softness. |

| Primary Purpose | Refine grains, homogenize, improve mechanical properties. | Soften, relieve stress, improve machinability. |

| Process Time/Cost | Shorter cycle, more energy-efficient (no furnace cooling). | Longer, more energy-intensive cycle. |

Guideline for Selection: If the primary need is maximum softness for heavy machining or cold forming, choose annealing. If the goal is to improve mechanical properties, refine grain structure after hot working, or prepare for final hardening, and a slight reduction in machinability is acceptable, normalizing is typically the more efficient and effective heat treatment process.

3.4 Industrial Applications of Normalizing

The normalizing heat treatment process is applied across numerous sectors:

- Forging Industry: Forgings are almost universally normalized to refine the coarse, non-uniform “as-forged” microstructure, ensuring consistent mechanical properties.

- Casting Industry: Steel castings are normalized to homogenize the dendritic structure, reduce segregation, and enhance ductility and impact resistance.

- Pre-Hardening Preparation: It is a standard preparatory step before surface hardening processes like carburizing, as it ensures a clean, fine-grained core structure.

- Final Treatment for Low-Carbon Steels: Many low-carbon steel structural components (e.g., beams, plates, bolts) are normalized as their final heat treatment process to achieve the required strength and toughness for service.

Part 4: The Science and Art of Quenching (Hardening)

4.1 The Purpose and Mechanism of the Quenching Heat Treatment Process

Quenching, or hardening, is the most intense of the four primary heat treatment process operations. It is defined by the rapid cooling of a metal from its austenitizing temperature. The singular, critical objective of the quenching heat treatment process is to achieve maximum hardness by inducing the formation of martensite.

The mechanism is kinetic: when austenite is cooled slowly, carbon atoms have time to diffuse out, forming softer phases like ferrite and cementite. During quenching, the cooling is so rapid that the carbon atoms are trapped within the iron lattice. This forces the face-centered cubic (FCC) austenite to undergo a diffusionless, shear transformation into a body-centered tetragonal (BCT) structure called martensite. The distorted BCT lattice and trapped carbon atoms create immense internal strain, which is the direct cause of martensite’s exceptional hardness. Importantly, the hardness of martensite increases directly with the carbon content of the steel.

4.2 The Quenching Procedure: Temperature, Media, and Techniques

A successful quenching heat treatment process requires precise control over several variables.

- Austenitizing Temperature: The steel must be heated into the fully austenitic phase field, typically:

- For hypoeutectoid steels: 30-50°C above the Ac3 line.

- For eutectoid and hypereutectoid steels: 30-50°C above the Ac1 line.

- Example: AISI 1045 steel (0.45% C) is austenitized at approximately 830-850°C.

- Quenching Media and Severity: The choice of quenching medium is paramount and is characterized by its quenching severity (H-value). Selection depends on the steel’s hardenability (alloy content) and part geometry.

- Water and Brine (Water + Salt): Provide very severe quenching (high H-value). Effective for simple shapes of plain-carbon steels but carry a high risk of distortion and cracking due to violent cooling and the formation of a vapor blanket. Brine breaks the vapor blanket more effectively, leading to more uniform cooling.

- Oil: The most common industrial quenchant. It provides a less severe, “softer” quench (moderate H-value). Oils cool rapidly through the temperature range where pearlite forms but more slowly through the martensite transformation range, reducing thermal and transformational stresses. Ideal for alloy steels and complex parts.

- Polymer Solutions (e.g., Polyalkylene Glycol – PAG): Aqueous solutions with adjustable cooling rates. By varying concentration and agitation, they can mimic the cooling profile of oil or fast oil, offering excellent control to minimize distortion.

- Gas Quenching (High-Pressure Nitrogen or Argon): Used in vacuum furnaces. Provides the slowest, most uniform quench and is essential for high-speed steels and high-alloy tool steels that are prone to distortion. Requires steels with very high hardenability.

- Agitation: Proper agitation of the quenchant is critical to break the insulating vapor blanket that forms around the hot part, ensuring uniform and repeatable cooling.

4.3 Understanding Hardenability: The Jominy End-Quench Test

A key concept related to quenching is hardenability—not to be confused with hardness. Hardness is a material’s resistance to indentation, while hardenability is a steel’s inherent ability to form martensite to a certain depth under a given quench condition.

Hardenability is primarily determined by the alloying elements (Mn, Cr, Mo, Ni, etc.), which delay the transformation of austenite to softer products, allowing martensite to form even with slower cooling rates (e.g., at the center of a thick section).

The standard test to measure hardenability is the Jominy End-Quench Test. A standardized bar is austenitized, placed in a fixture, and one end is quenched with a controlled water jet. Hardness is then measured at intervals along the bar’s length. The resulting “Jominy curve” is a powerful tool for material selection, allowing engineers to predict if a specific steel grade will through-harden in a given section size under their quenching heat treatment process.

4.4 Challenges, Defects, and Mitigation in Quenching

The violent thermal and transformational contractions during quenching generate tremendous residual stresses, leading to potential defects:

- Distortion and Warpage: Non-uniform cooling causes differential contraction, bending the part. Mitigation: Use less severe quenchants, optimize part design for uniform sections, agitate quenchant, and use fixtures (fixture quenching).

- Quench Cracking: Catastrophic fracture occurs when internal stresses exceed the brittle martensite’s fracture strength. Cracks often originate at sharp corners, holes, or surface defects. Mitigation: Avoid sharp design features (use generous radii), increase tempering temperature as soon as possible after quenching, and use martempering or austempering interrupted quench techniques.

- Soft Spots: Areas that fail to harden due to vapor blanket adherence or poor agitation. Mitigation: Ensure proper quenchant flow and agitation.

- Oxidation and Decarburization: Scale formation and loss of surface carbon during austenitizing, which destroys surface hardenability. Mitigation: Use atmosphere-controlled or vacuum furnaces.

The Cardinal Rule: A part that has undergone a quenching heat treatment process is in a highly stressed, brittle state and must never be placed into service without immediate subsequent tempering.

Part 5: Tempering – The Indispensable Follow-Up Process

5.1 The Role of the Tempering Heat Treatment Process

Tempering is the essential heat treatment process that invariably follows quenching. It involves reheating the as-quenched, martensitic steel to a temperature below the Ac1 transformation line, holding for a specified time, and then cooling, usually in air. While quenching provides hardness, tempering provides toughness and stability.

The necessity is absolute: quenched martensite, while extremely hard, is far too brittle for any structural or tooling application. It contains high internal stresses and is metastable. The tempering heat treatment process performs several vital functions:

- Relieves Quenching Stresses: The primary function, drastically reducing the risk of in-service cracking or premature failure.

- Improves Toughness and Ductility: It trades off some of the quenched hardness for a dramatic increase in impact resistance and plasticity.

- Stabilizes the Microstructure: It converts the unstable martensite and any retained austenite into more stable, tempered products.

- Achieves the Desired Final Property Balance: It is the master control knob for adjusting the final mechanical properties of the hardened steel.

5.2 Microstructural Transformations During Tempering

Tempering is a diffusion-controlled process where heating allows carbon atoms to move and the strained martensite lattice to relax. The transformations occur in stages:

- Stage I (Up to ~200°C): Precipitation of transition carbides (e.g., epsilon-carbide, η-carbide) from the carbon-supersaturated martensite. A slight decrease in hardness occurs, but significant internal stress relief begins.

- Stage II (~200-300°C): Decomposition of any retained austenite (untransformed austenite from quenching) into a mixture of ferrite and cementite, typically lower bainite.

- Stage III (Above ~300°C): The transition carbides dissolve, and stable cementite (Fe₃C) particles form and begin to coarsen. The martensite loses its tetragonal distortion and becomes ferrite. In this stage, hardness drops substantially while toughness increases markedly.

- Stage IV (Above ~500°C in some alloy steels): Further coagulation and spheroidization of cementite particles.

The final product is known as tempered martensite, a microstructure of fine cementite particles in a ferrite matrix.

5.3 Classification of Tempering by Temperature and Application

The tempering temperature is the most critical parameter, defining the final property suite:

- Low-Temperature Tempering (150–250°C):

- Purpose: To relieve quenching stresses and reduce brittleness while retaining most of the high hardness and wear resistance.

- Microstructure: Tempered martensite with fine transition carbides.

- Hardness: 58-65 HRC.

- Applications: Cutting tools, knives, bearings, precision gauges, and components subject to sliding wear.

- Medium-Temperature Tempering (350–500°C):

- Purpose: To achieve a high elastic limit (yield strength) and good fatigue resistance with moderate toughness.

- Microstructure: Tempered martensite with fine cementite.

- Hardness: 40-55 HRC.

- Applications: Coil springs, leaf springs, torsion bars, and die-casting dies.

- High-Temperature Tempering (500–650°C):

- Purpose: To produce an optimal combination of strength, ductility, and toughness—known as good “comprehensive mechanical properties.”

- Microstructure: Well-developed tempered martensite, often referred to as a sorbitic structure at the higher end.

- Hardness: 25-45 HRC.

- Applications: This is the “Tempering” in the critical “Quenching and Tempering” (Q&T or “调质”) process. Used for high-strength structural components: axles, crankshafts, connecting rods, gears, high-strength bolts, and machine tool spindles.

5.4 The Critical Combined Process: Quenching and Tempering (Q&T)

Quenching and High-Temperature Tempering is the most important combined heat treatment process sequence for engineering steels. Known as “调质处理” (Tempering treatment) in Chinese industry, its sole objective is to refine the grain and endow the steel with an excellent balance of high toughness and sufficient strength.

- Procedure: After rough machining, the component is fully austenitized, quenched to form martensite throughout its section (if hardenability allows), and then tempered at 500-650°C.

- Outcome: The resulting tempered martensite provides far superior mechanical properties—particularly impact toughness and fatigue strength—compared to a normalized or annealed microstructure of the same steel. It allows for lighter, more reliable designs.

- Typical Materials: Medium-carbon steels (e.g., AISI 1045, 4140, 4340) and medium-carbon alloy steels.

- Sequence in Manufacturing: Typically performed after rough machining but before final grinding or finishing, as the high-temperature tempering provides good dimensional stability.

Part 6: Process Selection, Sequencing, and Advanced Considerations

6.1 Guide to Selecting the Right Heat Treatment Process

Choosing the appropriate heat treatment process requires a systematic analysis of the component’s requirements. The following flowchart provides a strategic guideline:

6.2 Industrial Process Sequencing and Integration

A typical manufacturing route for a high-performance steel component integrates multiple heat treatment process steps strategically:

- From Raw Form (Forging/Casting): Forging -> Normalizing (to refine grain) -> Rough Machining -> Quenching -> Tempering -> Finish Machining/Grinding.

- From Annealed Stock: Machining (from pre-annealed bar) -> Quenching -> Tempering -> Grinding/Finishing.

- For High-Precision Parts: Rough Machine -> Stress Relief Anneal (to remove machining stress) -> Semi-Finish Machine -> Harden & Temper -> Final Grind/Polish.

Atmosphere Control: To prevent scaling and decarburization during heating, industrial furnaces use protective atmospheres (endothermic gas, nitrogen, argon) or vacuum. Vacuum heat treatment provides the highest quality surface and is standard for aerospace and premium tooling.

6.3 Advanced and Related Heat Treatment Processes

Beyond the “Four Fires,” several specialized heat treatment process techniques are crucial for advanced applications:

- Austempering: An interrupted quench where steel is cooled rapidly to a temperature above Ms (martensite start) and held in a salt bath to transform austenite to bainite. It provides good strength and ductility with minimal distortion.

- Martempering (Marquenching): An interrupted quench to a temperature just above Ms, followed by air cooling to form martensite. Its goal is to reduce thermal gradients and stresses during quenching, minimizing distortion and cracking risk.

- Surface Hardening: Techniques like Induction Hardening and Flame Hardening use rapid heating and quenching to harden only the surface layer of a part, leaving a tough core. Case Hardening processes like Carburizing and Nitriding add carbon or nitrogen to the surface before hardening, creating a hard, wear-resistant case.

Conclusion: The Synergy of the Four Fires

The four foundational heat treatment process techniques—annealing, normalizing, quenching, and tempering—are not isolated operations but interconnected tools in the metallurgist’s arsenal. Their power lies in strategic combination and precise application. Annealing and normalizing prepare the canvas, creating uniform, defect-free microstructures. Quenching applies the transformative stroke, creating extreme hardness. Finally, tempering performs the essential work of refinement, balancing properties and imparting practical usability.

Mastering this heat treatment process quartet requires more than memorizing temperature charts; it demands an understanding of the underlying materials science, heat transfer, and the practical realities of part design and production economics. From the normalized I-beam in a skyscraper to the quenched and tempered gear in a wind turbine, and the annealed drill blank on a factory floor, these processes form the invisible backbone of the modern engineered world. As materials continue to evolve, the fundamental principles of heating and cooling to control microstructure will remain the enduring foundation of manufacturing excellence. For any professional committed to creating durable, efficient, and reliable metal components, deep expertise in this essential heat treatment process family is not merely an advantage—it is an absolute necessity.