How To Operate A Wood CNC Machine?

Operating a wood CNC machine transforms digital designs into precise, tangible wooden components, a process that is both an art and a science. For clients in precision parts machining and customization, understanding this operation is crucial, even if your primary focus is metal. The principles of precision, programming, and process control are universally applicable, and mastering wood CNC operation can offer valuable insights into fixturing, toolpath strategies, and material behavior that complement high-tolerance metalworking.

This guide provides a comprehensive, step-by-step overview of operating a wood CNC machine, from initial setup to final part completion.

Phase 1: Pre-Operation Preparation & Design

Successful CNC operation begins long before the machine is powered on.

1. Design & File Preparation (CAD):

The process starts with a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) model. Using software like AutoCAD, Fusion 360, or SolidWorks, you create a precise 3D model of the part to be machined. For wood, considerations include grain direction (which affects strength and finish), inherent material movement, and the avoidance of overly thin, fragile features.

2. Toolpath Generation (CAM):

This is the critical bridge between design and machine. Using Computer-Aided Manufacturing (CAM) software, you import the CAD model and define how the CNC machine will create it.

Tool Selection: Choose appropriate router bits (end mills, ball noses, v-bits) based on the operation (roughing, finishing, engraving) and desired finish.

Defining Operations: Set up sequences like profiling (cutting the outline), pocketing (clearing areas), drilling, and 3D contouring.

Setting Parameters: This is where expertise shines. You must input:

Spindle Speed (RPM): The rotation speed of the cutting tool.

Feed Rate (IPM): The speed at which the tool moves through the material.

Depth of Cut: How much material is removed per pass.

Stepover: The overlap between toolpaths, crucial for surface finish.

Coolant/Lubrication: For wood, this is often compressed air to clear chips, though some operations may use minimal lubrication.

3. Post-Processing & G-Code:

The CAM software translates your toolpaths into G-code, a universal numerical control (NC) programming language that the CNC machine controller understands. This code contains every movement, speed, and tool change command.

Phase 2: Machine Setup & Workholding

1. Safety First:

Don safety glasses, hearing protection, and avoid loose clothing. Ensure the machine’s emergency stop is functional and the workspace is clear.

2. Material Securing (Workholding):

This is paramount for precision and safety. Wood can be held using:

Vacuum Table: Ideal for sheet goods (plywood, MDF), creating a uniform hold-down force.

Mechanical Clamps: Used for solid wood blocks or irregular pieces. Must be positioned outside the toolpath area.

T-Track Bed & Clamps: Offers flexible clamping options.

Double-Sided Tape: For very thin materials or non-through cuts.

3. Tool Installation & Zeroing:

Install the correct router bit into the collet, ensuring it is clean and tightened securely with a wrench.

Set the XYZ Zero Points:

X & Y Zero: Typically set to a designated corner or the center of the material.

Z Zero: The most critical. Using a touch probe or manual method (paper feeler gauge), set the Z-axis zero to the top surface of the workpiece. Inaccuracy here will ruin the part’s dimensions.

4. Load the G-Code:

Transfer the generated G-code file to the machine’s controller via USB, network, or direct connection. Visually simulate the toolpath on the controller’s screen if available to check for errors.

Phase 3: Execution & In-Process Monitoring

1. Dry Run:

Execute the program with the spindle off and the tool raised slightly above the workpiece (e.g., +10mm in Z). This verifies that the toolpath is correct, stays within the material bounds, and avoids collisions with clamps.

2. Commence Machining:

Start the dust collection system to maintain visibility and a clean work area.

Start the spindle and allow it to reach the programmed RPM.

Initiate the program.

Maintain Vigilant Observation: Monitor the first few passes closely. Listen for changes in sound—a high-pitched squeal may indicate too fast a feed or a dull bit; a deep rumble may suggest too slow a feed or too deep a cut. Watch for excessive vibration.

3. Managing Tool Changes:

For programs requiring multiple tools, the machine will pause. Follow the prompt to safely change the bit and re-establish the Z-zero for the new tool before resuming.

Phase 4: Post-Machining & Best Practices

1. Part Removal & Cleanup:

Once the cycle is complete and the spindle has stopped, carefully remove the part. Use tabs in your CAM design to keep parts from breaking free during cutting. De-burr or sand edges as needed.

2. Machine Maintenance:

Clean the machine bed, vacuum table, and surrounding area of all wood chips and dust. Regular maintenance of guide rails, ball screws, and the spindle is essential for long-term precision.

3. Optimization & Learning:

Evaluate the finished part. Are there tear-outs? The feed rate might be too slow, or you may need a down-cut spiral bit. Is the surface finish poor? Adjust the stepover or finishing pass parameters. Document what worked.

Conclusion

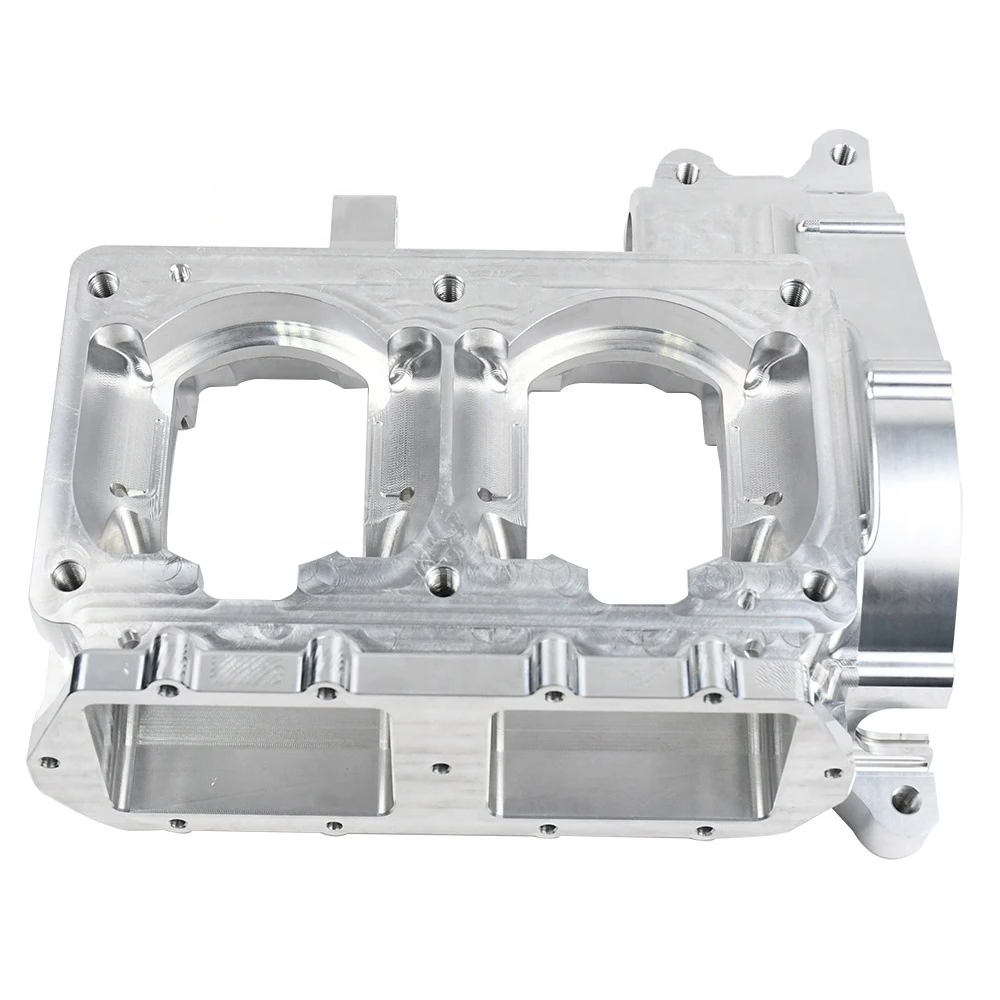

How to operate a wood CNC machine is a systematic discipline that parallels the demands of high-precision metal machining. It requires a blend of digital fluency (CAD/CAM), mechanical understanding (feeds/speeds, tooling), and meticulous process discipline (setup, monitoring). While wood is more forgiving than titanium, the pursuit of efficiency, accuracy, and flawless finish is identical. For businesses that demand this level of process mastery and reliability across materials—from prototyping intricate wooden molds to producing end-use metal components—partnering with a manufacturer that embodies this operational philosophy is key. This is where the expertise of a specialized partner like GreatLight CNC Machining Factory becomes invaluable. Their deep-rooted experience in managing advanced 5-axis CNC machining processes for metals translates into a fundamental understanding of precision operation that can inform and elevate any machining project, regardless of material.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What’s the main difference between operating a CNC for wood vs. metal?

A: The core principles are identical, but parameters differ drastically. Wood machining uses much higher feed rates and spindle speeds with lower cutting forces. Tooling is also different (router bits vs. end mills), and metal machining requires cutting fluid for cooling and lubrication, whereas wood primarily uses air for chip evacuation.

Q2: How do I prevent tear-out, especially on plywood or with delicate grain?

A: Use sharp, specialized bits. Down-cut spiral bits push the force downward, shearing the top fibers cleanly. Additionally, increasing your feed rate can sometimes produce a cleaner cut than a slow, grinding pass. Using a sacrificial backing board can also support the bottom fibers.

Q3: My cut edges are burned. What am I doing wrong?

A: Burn marks are typically caused by the tool rubbing instead of cutting, often due to a dull bit, too slow a feed rate, or too high an RPM. Try increasing your feed rate slightly, ensuring your bit is sharp, and verify your speed/feed calculations.

Q4: Is it necessary to use a vacuum hold-down system?

A: While not always necessary, it is highly recommended for sheet goods and repetitive work. It provides uniform clamping pressure across the entire sheet, allows for full utilization of the bed, and is much faster than mechanical clamping. For small, thick blocks, mechanical clamps are often sufficient.

Q5: How critical is dust collection during operation?

A: Extremely critical. Wood dust is a health hazard, a fire risk, and can interfere with machine operation by clogging moving parts, sensors, and the vacuum table. A high-quality dust collection system is non-negotiable for safe and professional operation.

Q6: Can the skills from operating a wood CNC translate to more industrial precision machining?

A: Absolutely. The foundational skills—understanding G-code, mastering CAD/CAM workflow, executing precise machine setup, and developing an intuition for tool-material interaction—are directly transferable. Moving to metals requires learning new materials, tighter tolerances, and different tooling, but the operational mindset is the same. Manufacturers that excel in high-tolerance fields, such as GreatLight CNC Machining Factory, operate on these universal principles of precision and control. For a deeper look at advanced applications of these principles, you can explore industry insights on platforms like LinkedIn.