The Art and Science of Machining Elegant Script: A Comprehensive Guide

For designers, engineers, and manufacturers, the desire to incorporate elegant, flowing script fonts into a product—be it a commemorative plaque, a luxury brand logo, a personalized gift, or a high-end interface component—is common. However, the transition from a beautiful digital typeface to a perfectly machined physical feature is fraught with technical pitfalls. Unlike blocky, sans-serif fonts, script fonts, with their connected strokes, variable line weights, and delicate serifs, present a unique set of challenges for CNC machining. This article delves into the core principles and advanced techniques required to successfully get script fonts to cut cleanly and beautifully on a CNC machine, transforming design intent into manufacturing reality.

Understanding the Core Challenge: Why Script Fonts Are Difficult

At its heart, the difficulty lies in the fundamental conflict between the font’s design geometry and the physical properties of the machining process.

Tool Geometry vs. Font Geometry: A CNC end mill is a cylindrical cutter. It cannot produce sharp internal corners—these will always have a radius equal to the tool’s radius. Script fonts often have tight, acute angles where strokes meet or terminate. A standard tool will leave a rounded fillet, destroying the font’s sharp, crisp aesthetic.

Chip Evacuation and Tool Pressure: The continuous, often narrow, paths of script fonts can trap cutting chips, especially when engraving or doing V-carving. Poor chip evacuation leads to recutting, increased heat, tool deflection, and a poor surface finish—often melting plastic or galling aluminum.

Tool Deflection and Line Width Consistency: The thin, graceful upstrokes and thick downstrokes of a script font require precise depth control. A tool flexing under load (deflection) will cut wider and shallower than programmed, ruining the line weight variation that gives the font its character.

Material Considerations: The optimal strategy for machining script into hardened steel is vastly different from that for acrylic, aluminum, or wood. Brittle materials can chip, soft materials can burr, and stringy materials can wrap around the tool.

A Step-by-Step Methodology for Success

Achieving perfect results requires a systematic approach, from digital preparation to machine execution.

Phase 1: Intelligent Design and Font Preparation (The Digital Foundation)

This is the most critical phase, where 80% of potential problems can be eliminated.

H3: Choosing or Modifying the Right Font

Avoid Ultra-Thin Strokes: If the design allows, select a script font with a minimum stroke width that is at least 1.5 times the diameter of the smallest tool you plan to use. This provides a margin for error.

Simplify Where Possible: Using vector software (like Adobe Illustrator or CorelDRAW), examine the font outlines. Often, script fonts have excessive nodes and overly complex curves. Use the “simplify” function judiciously to reduce the node count without altering the form. Cleaner paths lead to smoother tool movements and smaller G-code files.

Manually Address Problem Areas: Zoom in on junctions and tight curves. You may need to slightly open up tight corners or modify areas where strokes converge to prevent tool interference. This is often called “design for manufacturability” (DFM) for text.

H3: The Critical Role of Toolpath Generation (CAM Software Strategy)

Engraving vs. V-Carving vs. Pocketing:

Engraving: Uses a pointed V-bit or ball-nose end mill to trace the centerline of the font. Excellent for reproducing true line weight variation but requires a very stable machine and precise depth control.

V-Carving: Uses a V-bit where the width of the cut is determined by the depth. This is fantastic for script fonts as a single tool can create both thin and thick lines based on the vector’s outline. It’s the most common and effective method for decorative script.

Pocketing: Clears out the area of the letters. Generally not ideal for script due to the need for very small tools to get into tight areas, leading to long machining times and potential tool breakage.

Lead-In and Lead-Out: Program gentle, arcing lead-in moves into the cut, rather than plunging directly onto the font line. This prevents tool marks at the start of each stroke.

Optimized Cutting Order: Sequence the toolpath so that the tool moves continuously along connected strokes where possible, minimizing lifts and travels. This improves finish and reduces cycle time.

Phase 2: Tooling and Machine Setup (The Physical Execution)

H4: Tool Selection is Paramount

V-Bits (for V-Carving): The go-to choice. A 60-degree or 90-degree V-bit with a sharp, polished tip can produce exquisite results. For metals, use a solid carbide V-bit with a coating (like TiAlN) for wear resistance.

Ball Nose End Mills (for 3D Contouring): If the script is part of a curved surface, a small ball nose end mill (e.g., 1mm or 2mm radius) can follow the 3D toolpath. The smaller the ball, the better the detail, but the higher the risk of breakage.

Micro End Mills: For very small, deep script or in hard materials, you may need micro-diameter end mills (0.3mm – 1.0mm). These require high spindle speeds, minimal runout, and very light chip loads.

H4: Machine Parameters and Technique

High Spindle Speed, Low Feed Rate: This is the golden rule for fine detail. A high RPM ensures a clean shearing action, while a low feed rate reduces tool pressure and deflection.

Climb Milling vs. Conventional Milling: For most finishing passes on fonts, climb milling (where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed) typically provides a better surface finish on the side of the cut, which is critical for the letter’s edge quality.

Multiple Passes: Never attempt to cut the full depth in one pass, especially with small tools. Use multiple, light step-down passes (e.g., 0.1mm-0.2mm per pass in aluminum) to maintain accuracy and control chip load.

Rigidity is Key: Ensure the workpiece is securely fixtured. Any vibration will be reflected in poor edge quality. For thin materials, use a spoil board and adhesive to dampen vibration.

Advanced Techniques for Flawless Results

Tapered Ball Nose End Mills: For deep 3D script, a tapered tool offers greater strength at the shank while maintaining a fine tip, reducing deflection.

High-Speed Machining (HSM) Toolpaths: Modern CAM software can generate “smooth” or “morphing” toolpaths that maintain a more constant tool load and use arc movements instead of short line segments, resulting in a glass-smooth finish on the font walls.

Adaptive Clearing for Pocketed Text: If you must pocket, use adaptive clearing strategies that keep the tool engaged in material with a consistent chip load, protecting small tools.

Post-Processing: Sometimes, a perfect machined finish requires a manual touch. A light hand-deburring with an abrasive cord or a specialized stone can remove minute burrs from metal letters. For plastics, a quick pass with a fine flame polisher can restore clarity to the edges.

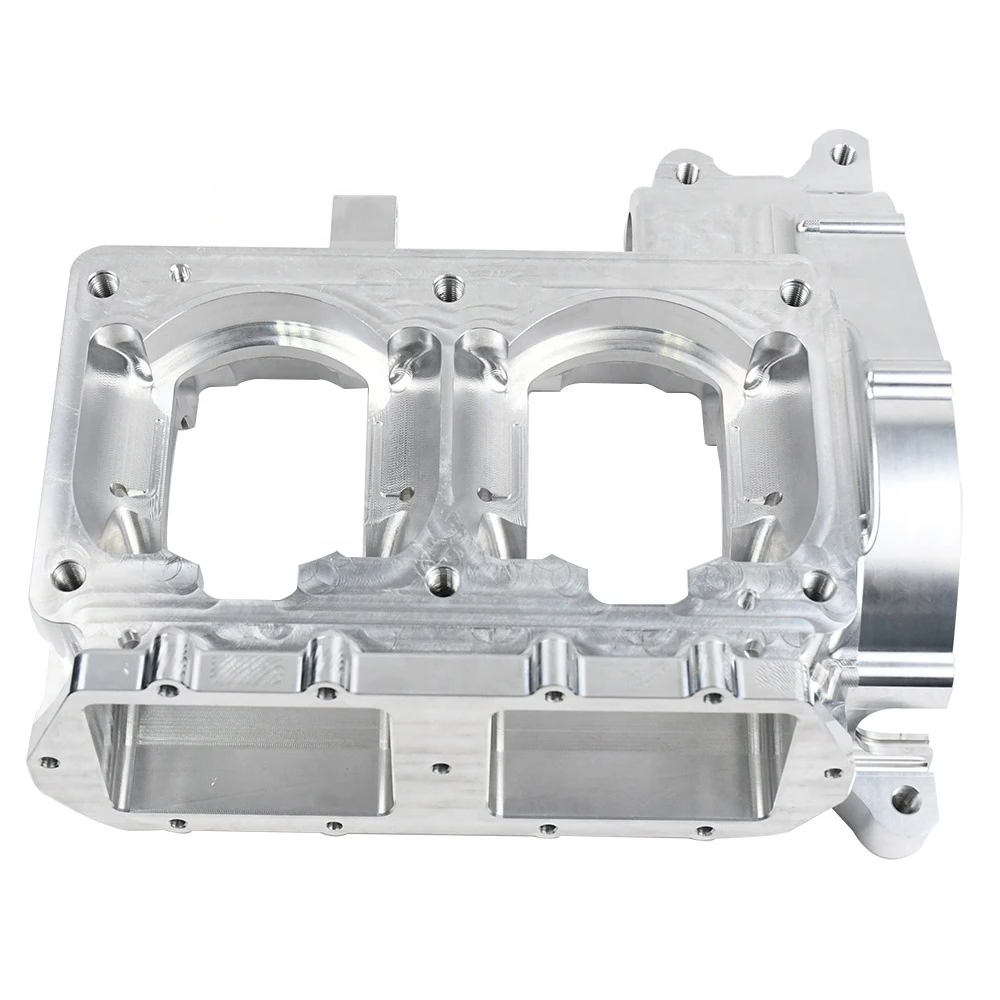

Case in Point: GreatLight Metal’s Approach to Precision Typography in Hardware

In the realm of high-stakes manufacturing—where a serial number on a medical device or a logo on an aerospace component must be immaculate—the challenge of machining fine script is amplified. GreatLight Metal encounters this regularly when producing custom components for luxury automotive interiors, specialized scientific instrumentation, and high-end consumer electronics.

Their success hinges on the integrated pillars mentioned in their brand narrative: advanced equipment and deep engineering support. For a recent project involving a titanium alloy housing requiring a deeply engraved, intricate script logo, their engineers didn’t just select a font and run a standard toolpath. They engaged in a full DFM review:

Collaborative Redesign: They worked with the client’s designer to slightly adjust the stroke junctions of the script to accommodate a robust 0.5mm tapered carbide engraving tool, ensuring longevity for a production run of thousands of parts.

Process Design: They chose a precise V-carving operation followed by a secondary light ball-nose finishing pass along the 3D contour of the letters to achieve a specific reflective quality.

Process Validation: Before machining the costly titanium blanks, they tested the entire toolpath sequence on a analog material using their in-house SLA 3D printer to produce a photopolymer resin prototype. This allowed for visual verification of the script’s form and legibility without any material waste.

This systematic, technology-integrated approach, backed by their ISO 9001:2015 certified quality management system, ensures that the “precision promise” of the digital font is translated without loss into the physical part. It demonstrates that getting script fonts to cut perfectly is not a matter of luck, but of applying rigorous engineering discipline to an artistic element.

Conclusion

Getting script fonts to cut cleanly on a CNC machine is a compelling intersection of art and engineering. It demands more than just loading a file and pressing start. It requires a thoughtful journey from intelligent font selection and vector preparation, through strategic CAM programming, to the meticulous selection of tooling and machining parameters. By understanding the inherent challenges—tool geometry, chip evacuation, and material behavior—and applying a structured methodology, manufacturers can consistently produce elegant, precise engraved text. As demonstrated by advanced manufacturers, the most reliable path to success involves treating decorative text with the same level of engineering scrutiny as any other critical feature, leveraging both advanced technology and deep collaborative expertise to guarantee a flawless result.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

H3: Q1: What is the single most important factor in successfully cutting script fonts?

A: Digital Preparation. Choosing a suitable font and then optimizing its vector paths for manufacturability (opening tight corners, simplifying nodes) sets the stage for success. A perfect toolpath cannot fix a poorly prepared design.

H3: Q2: Can I use any script font I download for CNC machining?

A: Not directly without inspection. Many decorative fonts are designed for print and have artistic details (extremely thin hairlines, overlapping strokes, texture) that are physically impossible to machine. You must evaluate and often modify the vector outlines to create a “machinable” version.

H3: Q3: V-bit or ball nose end mill—which is better for script?

A: For 2D or 2.5D engraving on a flat surface, a V-bit is generally superior and more efficient, as it naturally creates variable line widths. A ball nose end mill is essential for true 3D script that follows a contoured surface, or for creating a rounded profile at the bottom of an engraving.

H3: Q4: How do I prevent chipping when machining script into brittle materials like acrylic or wood?

A: Use very sharp, polished tools (single or two-flute). Employ climb milling for a cleaner shear. Increase spindle speed and reduce feed rate. For acrylic, consider using a compression spiral end mill if doing pocketing, as it shears the top and bottom layers cleanly. Sometimes, applying painter’s tape to the surface can also help reduce edge chipping.

H3: Q5: My script looks good in aluminum but terrible in stainless steel. What changes should I make?

A: Stainless steel is tougher and gummier. You need to:

Use sharp, carbide tools specifically designed for stainless (e.g., with a sharp edge prep and lubricious coating).

Reduce feed per tooth significantly while maintaining adequate chip load to avoid work hardening.

Ensure flood coolant or high-pressure mist is directed precisely at the cutting edge to control heat and evacuate chips.

Consider a post-process electropolish or vibratory tumble to remove micro-burrs and enhance the appearance of the engraved script.