In the realm of modern woodworking, the transition from hand tools to computer-controlled precision represents a fundamental leap. At the heart of this transformation lies the wood CNC machine, a sophisticated piece of equipment that has revolutionized how we design, prototype, and produce everything from custom furniture to intricate architectural millwork. For clients seeking precision parts machining and customization, understanding the operational principles of these machines is crucial, as the core concepts of digital fabrication translate directly across materials, from wood to metals and composites.

This article delves into the mechanics, processes, and technological nuances of how wood CNC machines function, providing a comprehensive guide for manufacturers, designers, and engineers.

H2: The Core Principle: Translating Digital Design into Physical Form

At its essence, a wood CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine is a subtractive manufacturing system. It starts with a solid block or sheet of material—in this case, wood, MDF, plywood, or composites—and uses computer-controlled cutting tools to remove material, precisely carving out the desired part based on a digital 3D model (CAD file).

The workflow follows a clear, automated chain:

Design (CAD): A part is designed in Computer-Aided Design software (e.g., AutoCAD, Fusion 360, SolidWorks, or specialized software like VCarve).

Toolpath Generation (CAM): The CAD file is imported into Computer-Aided Manufacturing software. Here, the programmer defines the machining strategy: selecting tools, setting cutting speeds, feed rates, depth of cuts, and generating the precise toolpaths (the G-code) that the CNC machine will follow.

Machine Setup: The appropriate wood stock is secured to the machine bed using clamps, vacuum tables, or fixtures. The required cutting tools (end mills, ball nose bits, v-bits) are loaded into the machine’s spindle.

Execution (CNC Control): The G-code is sent to the machine’s controller. The controller interprets the code and precisely coordinates the movement of the spindle (holding the tool) along the X, Y, and Z axes, cutting the material with high accuracy and repeatability.

Finishing: The machined part is removed, often requiring secondary post-processing like sanding, assembly, or finishing with stains and sealants.

H3: Key Components of a Wood CNC Machine

Understanding the hardware is key to appreciating its capabilities:

The Frame & Bed: Provides rigid, vibration-dampening support. Heavier frames offer greater stability for high-precision work.

Motion System: Typically uses linear guides or rails and ball screws for smooth, precise movement along the axes.

The Spindle: The motor that rotates the cutting tool. High-frequency spindles (often liquid-cooled) maintain constant RPM under load, crucial for clean cuts in hardwoods.

Cutting Tools (Bits): The “business end” of the operation. A vast array exists:

End Mills: For profiling, pocketing, and cutting out parts.

Ball Nose Bits: For 3D contouring and sculpting.

V-Bits: For V-carving lettering and decorative lines.

Compression Bits: Designed to cut cleanly on both the top and bottom surfaces of sheet materials like plywood, preventing tear-out.

The Controller: The machine’s “brain.” It reads the G-code and drives the motors. Advanced controllers allow for touch-off probes for tool measurement and workpiece zeroing.

Workholding: Methods to secure the material. Vacuum tables are extremely common in woodworking, using suction to hold down large sheets flat across the entire bed.

H2: The Machining Processes in Wood CNC Operations

A single wood CNC machine can perform multiple distinct operations, which are programmed as separate toolpaths in the CAM software.

H3: 1. Profiling (Contour Cutting)

This is the process of cutting the outer shape of a part from the stock material. The tool follows the part’s perimeter, often cutting completely through the material. For internal cutouts (like the center of a letter ‘O’), the machine will first drill a pilot hole for the tool to plunge into.

H3: 2. Pocketing

This involves clearing out material from within a defined boundary to a specific depth, creating a recessed area. It’s used for inlays, joinery slots (e.g., for loose tenons), or decorative panels. Strategies include:

Adaptive Clearing: Efficiently removes large volumes of material while maintaining constant tool engagement, protecting the tool and the wood.

Raster/Pocket Clearing: Moves back and forth in parallel passes to clear the area.

H3: 3. Drilling & Boring

While a router bit can plunge, dedicated drilling cycles are used for creating precise, clean holes for dowels, hardware, or ventilation. Some CNC machines are equipped with automatic tool changers (ATCs) that can switch from a routing bit to a drill bit for optimal results.

H3: 4. 3D Carving & Relief Machining

This is where wood CNC machines showcase their artistic potential. Using a ball nose bit, the machine moves simultaneously along the X, Y, and Z axes to sculpt complex, organic 3D shapes from a thicker block of wood. The toolpath is generated from a 3D model (like an STL file), with the CAM software calculating the necessary step-over distances to create a smooth surface finish.

H3: 5. Engraving & V-Carving

Using V-shaped bits, the machine creates decorative grooves whose width varies with depth. This is ideal for sign-making, intricate line art, and decorative borders. The angle of the bit determines the line characteristics.

H2: Critical Technical Considerations for Optimal Results

Moving from concept to flawless finished part requires attention to several technical factors:

Tool Selection & Speeds/Feeds: The wrong bit or incorrect speed (RPM) and feed rate (how fast the tool moves through the material) can lead to burning, tear-out, poor finish, or broken tools. Hardwoods like maple or oak require different parameters than softwoods like pine or sheet goods like MDF.

Climb vs. Conventional Milling:

Climb Milling: The cutter rotates in the same direction as the feed. This generally provides a cleaner finish on the machined edge of wood but can be more demanding on the machine.

Conventional Milling: The cutter rotates against the feed direction. It’s often more forgiving on the tool and machine but may produce a slightly rougher edge.

Dust Collection: Wood machining produces immense amounts of dust and chips. An integrated high-power dust collection system is non-negotiable for maintaining a clean work environment, ensuring tool visibility, protecting machine components, and safeguarding operator health.

Material Characteristics: Wood is anisotropic—its properties (hardness, grain direction) vary. Programming must account for grain direction to minimize tear-out, especially on cross-grain cuts.

H2: From Wood to Metal: The Parallels in High-Precision Machining

While the material changes, the fundamental principles of CNC machining remain strikingly consistent. This is where the expertise of a full-service manufacturer becomes invaluable. The same core competencies in CNC programming, toolpath optimization, workholding ingenuity, and precision process control that produce a flawless carved oak door panel are directly applicable to machining a complex aluminum aerospace bracket or a medical-grade titanium implant.

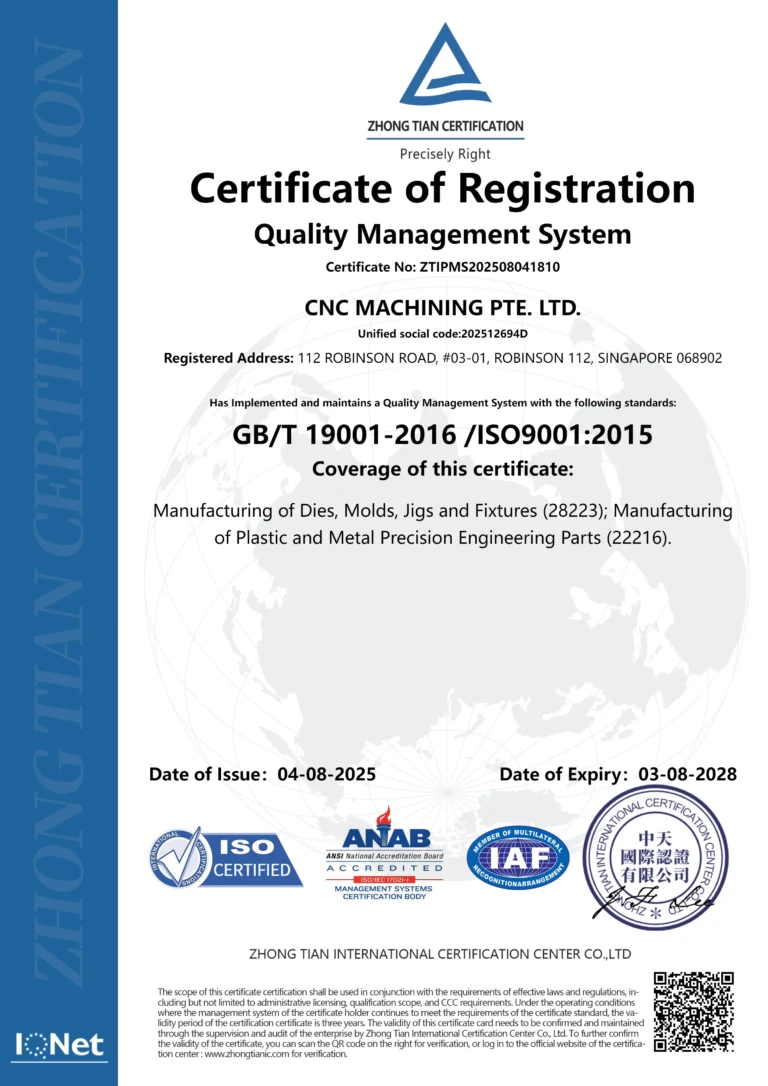

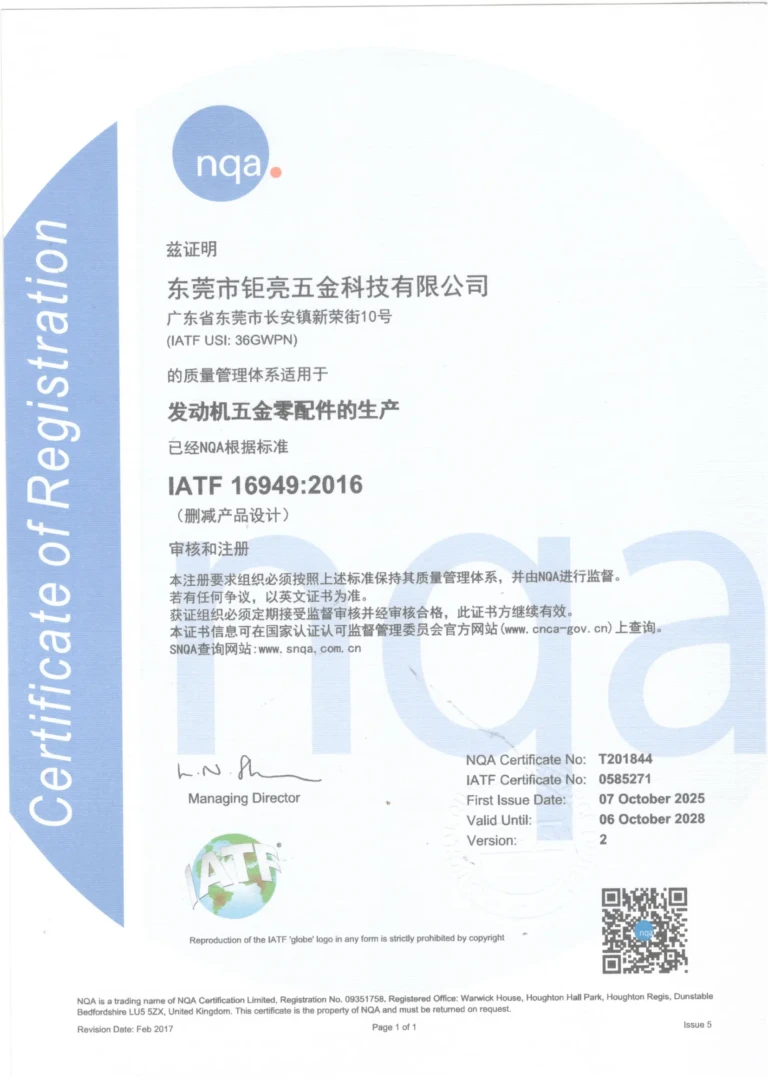

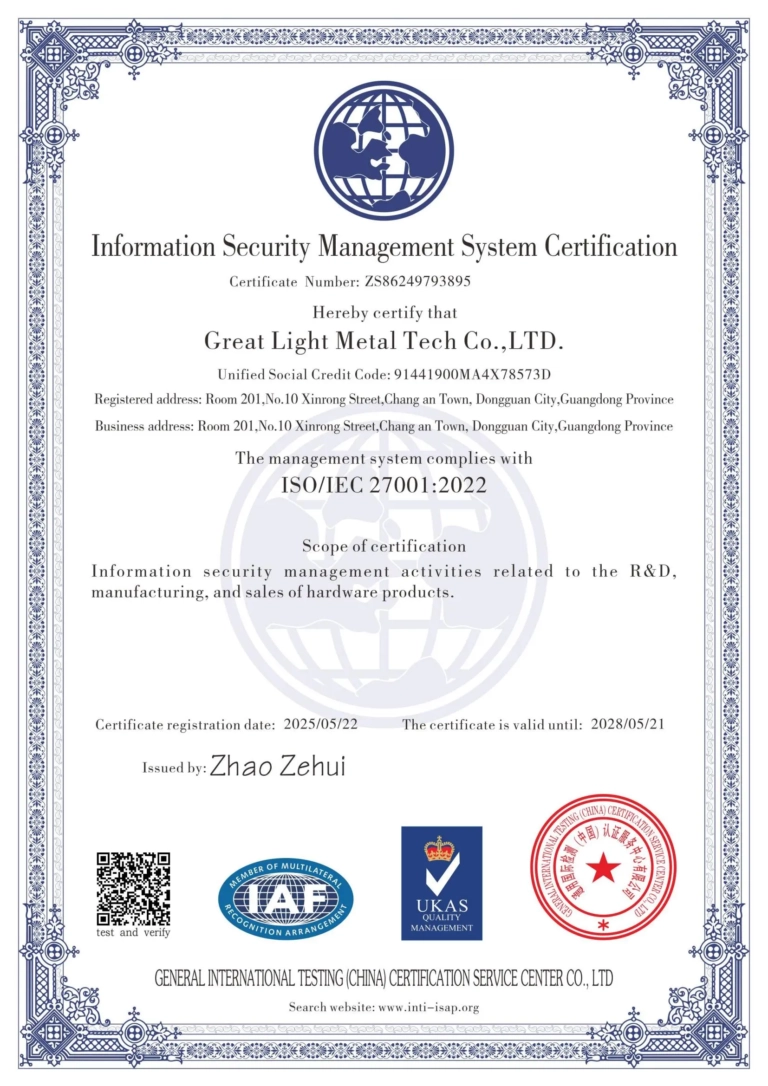

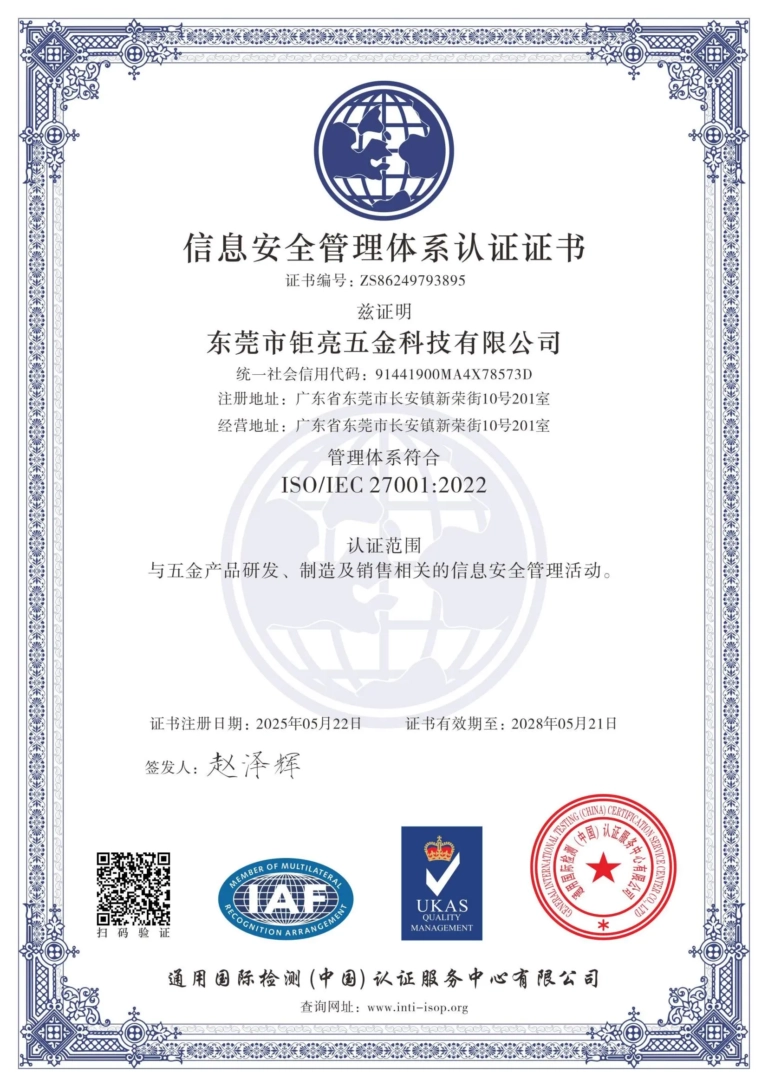

For instance, a manufacturer like GreatLight CNC Machining Factory leverages this cross-material expertise. Their advanced five-axis CNC machining capabilities, essential for complex 3D forms in metal, are conceptually identical to the 3D carving operations in wood—just executed with vastly more rigid machines, different cutting tools (carbide or diamond), and often with coolant. Their rigorous approach to ISO 9001:2015 certified quality management ensures that whether the material is walnut or tungsten, the process is controlled, documented, and repeatable to meet exacting specifications.

Conclusion

How do wood CNC machines work? They operate as the precise, automated intersection of digital design, mechanical engineering, and material science. By understanding the components—from the rigid frame and high-speed spindle to the critical CAM software—and the core processes like profiling, pocketing, and 3D carving, one gains a deep appreciation for their transformative power in woodworking.

This knowledge also builds a bridge to the broader world of precision manufacturing. The discipline, planning, and technical mastery required to successfully run a wood CNC operation are the very same skills that underpin high-tolerance metal machining. For businesses looking to source custom parts, partnering with a manufacturer that demonstrates mastery over these universal CNC principles, across a wide range of materials and processes, is the key to turning innovative designs into tangible, high-quality reality.

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions About Wood CNC Machines

H3: Q1: What’s the main difference between a CNC router for wood and a CNC mill for metal?

A: The primary differences are in rigidity, power, and spindle design. Metal CNC mills are built with extremely heavy, robust frames to withstand higher cutting forces. They use spindles designed for lower RPM but higher torque and almost always employ cutting fluid (coolant). Wood CNC routers are optimized for high RPM (often 18,000-24,000 RPM) to achieve clean cuts in fibrous material and prioritize large work envelopes for sheet goods.

H3: Q2: Can a wood CNC machine cut aluminum or plastic?

A: Many higher-end wood CNC routers can successfully machine soft metals like aluminum and plastics, especially with proper tooling (single-flute end mills for aluminum) and reduced feed rates. However, it is not their primary design purpose, and production volume or high-precision metal work should be handled by a dedicated metal machining center.

H3: Q3: What software is needed to operate one?

A: You need a full stack: CAD software for design (e.g., Fusion 360, SketchUp), CAM software to generate toolpaths from the design (e.g., VCarve Pro, Fusion 360’s CAM module, Mastercam), and control software that runs on the machine itself to execute the G-code (e.g., Mach3, GRBL, or proprietary controllers).

H3: Q4: How important is dust collection?

A: It is absolutely critical. Wood dust is a significant fire hazard and a health risk (respiratory issues). Effective dust collection preserves machine accuracy, keeps tools cool and visible, and ensures a safe workshop environment. It is not an optional accessory.

H3: Q5: For a professional custom part requiring both wooden and metal components, what’s the best approach?

A: The most efficient and quality-assured approach is to partner with a manufacturing service provider that offers integrated capabilities. A supplier like GreatLight CNC Machining Factory can handle the complete assembly. They can precision machine the metal components using their five-axis CNC machining services and fabricate the complementary wooden parts, ensuring perfect fit, finish, and a single point of accountability for the entire project, backed by their ISO 9001:2015 certified quality system. For insights into how such a company operates on a professional scale, you can explore their profile on LinkedIn{:target=”_blank”}.