The Unseen Guardian of Precision: Why CNC Measuring Equipment is Non-Negotiable in Modern Manufacturing

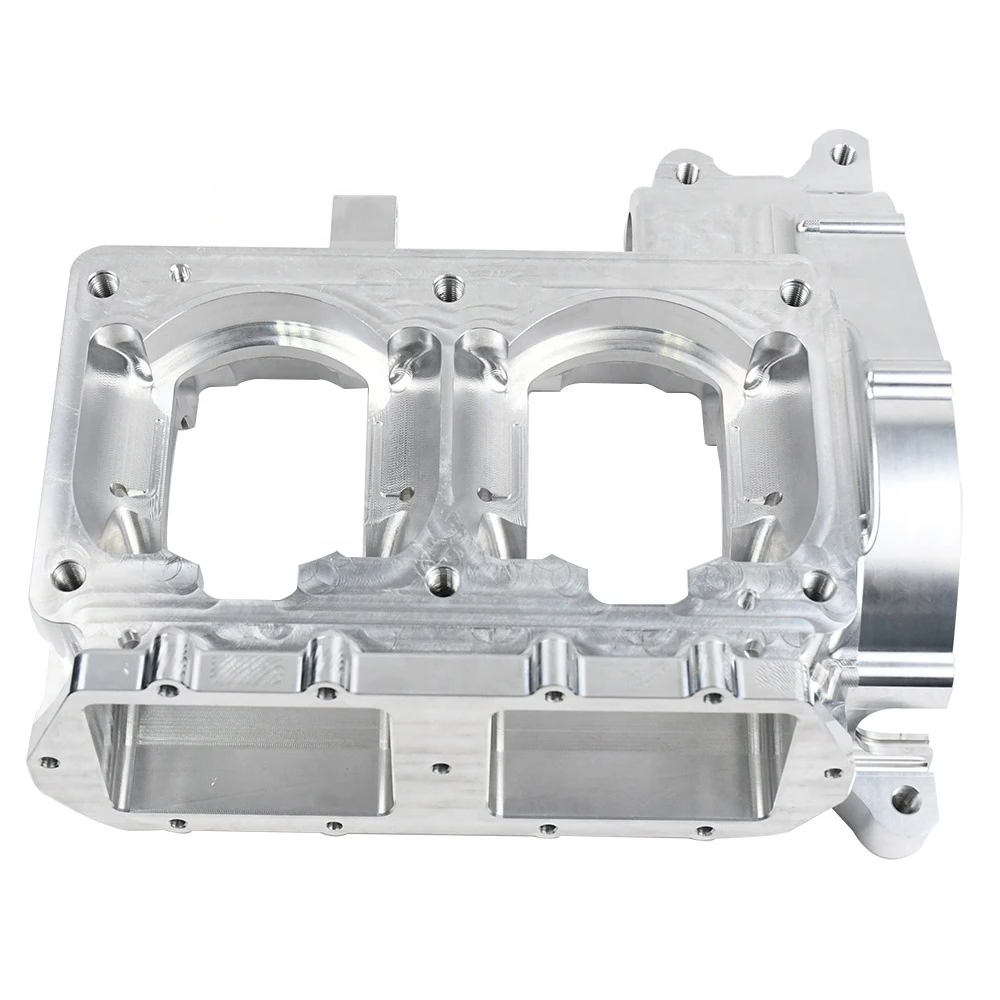

In the relentless pursuit of manufacturing excellence, the spotlight often shines brightest on the machines that create – the CNC mills, lathes, and routers that transform raw materials into intricate components. Yet, lurking behind the scenes, a critical category of technology works tirelessly to ensure these creations meet the unforgiving standards of precision demanded by industries like aerospace, medical devices, and automotive. This unsung hero is the realm of CNC Measuring Equipment. Far from being mere tools, they are the guardians of quality and repeatability, the silent partners enabling the high-precision results that define modern production.

Beyond the Machine: The Critical Role of Measuring Equipment

While the CNC machine performs the cutting, turning, and shaping, it operates based on programmed instructions. The ultimate quality of the finished part hinges on the accuracy of those instructions and the machine’s ability to faithfully execute them. This is where CNC Measuring Equipment steps in, performing several indispensable functions:

- Verifying Program Accuracy: Before the first part is cut, a critical step involves using Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) or laser trackers to check the machine’s program against the intended geometry. This is known as a "program verification" or "machine calibration check." It catches errors in tool paths or program generation early, preventing costly scrap and rework on expensive materials. Imagine building a house without checking the foundation blueprint first – measuring equipment provides that foundational verification for CNC operations.

- Ensuring Dimensional Accuracy: This is perhaps the most critical function. CMMs, especially those integrated with CNC systems (CMMs on Machine tools – CMMs), probe the actual manufactured part against the original CAD model. They measure key dimensions, features, tolerances, and geometric relationships (like concentricity or parallelism). The system compares the measured data to the design tolerances. Any deviations trigger immediate correction signals, allowing operators or automated systems to adjust machining parameters, recalibrate tools, or reject non-conforming parts. It’s the constant feedback loop ensuring the machine’s output matches the design intent with micrometer-level accuracy.

- Monitoring Machine Health and Performance: Advanced measuring equipment like laser trackers or optical comparators can monitor the machine’s performance over time. They track the wear of cutting tools, the backlash in joints, or the potential drift of linear axes. By identifying these subtle degradations early, preventative maintenance can be scheduled, avoiding catastrophic failures and maintaining consistent part quality throughout a production run. It’s like a health check for the machine itself.

- Qualifying Fixtures and Jigs: Precision fixtures and jigs are vital for holding parts correctly during machining. Measuring equipment ensures these fixtures themselves meet the required geometric tolerances (e.g., flatness, squareness, runout) before they are used. This ensures the part is held accurately, which directly impacts the accuracy of the final machined feature.

Types of CNC Measuring Equipment: Tools of the Trade

The landscape of CNC measuring equipment is diverse, each type suited for specific tasks:

- Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs):

- Manual (Manual Probing): Operator positions the probe manually or with a crane to touch probe features.

- Manual (Automated): Machine positions the probe based on a programmed path.

- Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs): Fully automatic machines using multi-axis robotic arms to probe parts rapidly and repetitively with high precision (often sub-micron). These are the workhorses for high-volume dimensional inspection.

- Optical Comparators: Utilize high-intensity light and magnifying lenses to project a magnified image of a part onto a screen. The operator compares this image to a template or master part, checking form, size, and contour. Excellent for simple form checks and visual comparison.

- Laser Trackers: Handheld or fixed devices projecting a laser beam onto reflectors mounted on the part or fixture. They capture high-precision spatial coordinates over large volumes (hundreds of meters). Crucial for measuring large parts, tooling, fixtures, and monitoring machine tool geometry in large-scale manufacturing.

- Vision Systems (Vision Measurement Systems – VMS): Use high-resolution cameras and software to capture 2D or 3D images of parts. Ideal for surface finish analysis, feature detection on complex shapes, and automated sorting based on visual criteria.

- Machine Tool Probes (On-Cut or On-Machine): Integrated into CNC machines, these probes touch the workpiece or tool holder during operation to measure dimensions during cutting. This enables "in-process" adjustment, dynamically compensating for tool wear or thermal effects in real-time, maximizing dimensional accuracy and tool life. This is a key technology enabling high-speed machining of precision parts.

- Form Error Checkers (FECs): Specialized systems combining coordinate measuring data with advanced analysis software to quantify and visualize complex geometric deviations like circularity, cylindricity, and squareness.

Integration: The Seamless Flow of Data

The true power of CNC measuring equipment lies not just in the machines themselves, but in their seamless integration with the broader manufacturing ecosystem. Modern systems communicate effortlessly via standards like CAD/CAM data formats (e.g., STEP, IGES) and machine tool communication protocols. Probe data is fed directly back into the CNC control software. CMM data is uploaded to ERP/MES systems for traceability and statistical process control (SPC). This integration creates a closed-loop process where measurement informs machining, ensuring every part produced is a mirror image of the design intent.

Conclusion: The Foundation of Trust

In the competitive landscape of precision manufacturing, CNC Measuring Equipment is far from optional; it’s foundational. It provides the irrefutable evidence that a part meets specifications, builds trust with customers demanding reliability, and drives continuous improvement. From catching program errors before they escalate to dynamically compensating for machine wear during production, these tools are indispensable partners to the CNC machines that create. Investing in advanced measuring technology is an investment in quality, efficiency, and ultimately, customer confidence. Without the vigilant eye of precise measurement, even the most sophisticated CNC machine remains an untested artist, capable of creation but uncertain of perfection.

FAQs About CNC Measuring Equipment

Q: What is the most common type of CNC measuring equipment?

A: Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs), particularly automated CMMs for high-volume inspection, are the most prevalent type used in precision manufacturing for dimensional verification.

Q: Do I really need a CMM? Can’t I just use calipers or a ruler?

A: While simple tools like calipers are useful for quick checks, they lack the precision, automation, speed, and comprehensive capability of CMMs. CMMs can measure complex geometries, internal features, and multiple points simultaneously to micron or sub-micron tolerances, providing objective, documented proof of quality that meets modern engineering standards.

Q: How often should CNC measuring equipment be calibrated?

A: Calibration schedules are highly dependent on the equipment’s usage and industry standards. Critical CMMs used for first-article inspection might require weekly calibration, while less critical systems might have monthly or quarterly schedules. Manufacturers should follow the equipment manufacturer’s recommendations and industry-specific requirements (e.g., AS9100 for aerospace).

Q: What is the difference between on-machine probing and off-line CMM inspection?

A: On-machine probing (often called "in-process inspection") occurs during the machining cycle. The probe checks dimensions while the part is being cut, allowing for real-time adjustments. Off-line CMM inspection happens after the part is complete, typically at a separate inspection station. Both are vital; on-machine for dynamic quality control during production, off-line for comprehensive verification and record-keeping.

Q: Can measuring equipment measure surface finish?

A: Yes, specialized equipment like Form Error Checkers (FECs) and advanced CMMs or CMM probes equipped with specific surface finish probes can measure parameters like roughness (Ra, Rz), waviness, and form error to quantify the texture of a surface. Vision systems can also assess certain finish aspects visually.

Q: How expensive is CNC measuring equipment like CMMs?

A: Costs vary significantly based on the type, size, precision level, and automation. Basic manual CMMs might start in the low five figures, while advanced automated CMMs for large components can cost over six figures. The return on investment comes from drastically reducing scrap and rework, ensuring product quality, and enabling high-precision manufacturing capabilities.

Q: Can one machine handle all measuring tasks?

A: A comprehensive facility might use multiple types: CMMs for detailed dimensional checks, laser trackers for large parts and machine alignment, vision systems for surface and assembly verification. The choice depends on the specific needs of the components and processes being monitored.