In the world of modern manufacturing, where microns define success and complex geometries are the norm, the Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machine stands as the undisputed workhorse. From the aerospace components soaring overhead to the medical implants sustaining life within, the precise, repeatable, and automated operation of CNC machining is foundational. But for clients and engineers sourcing precision parts, understanding how a CNC machine works transcends casual curiosity—it’s key to specifying requirements, evaluating supplier capabilities, and ultimately ensuring project success.

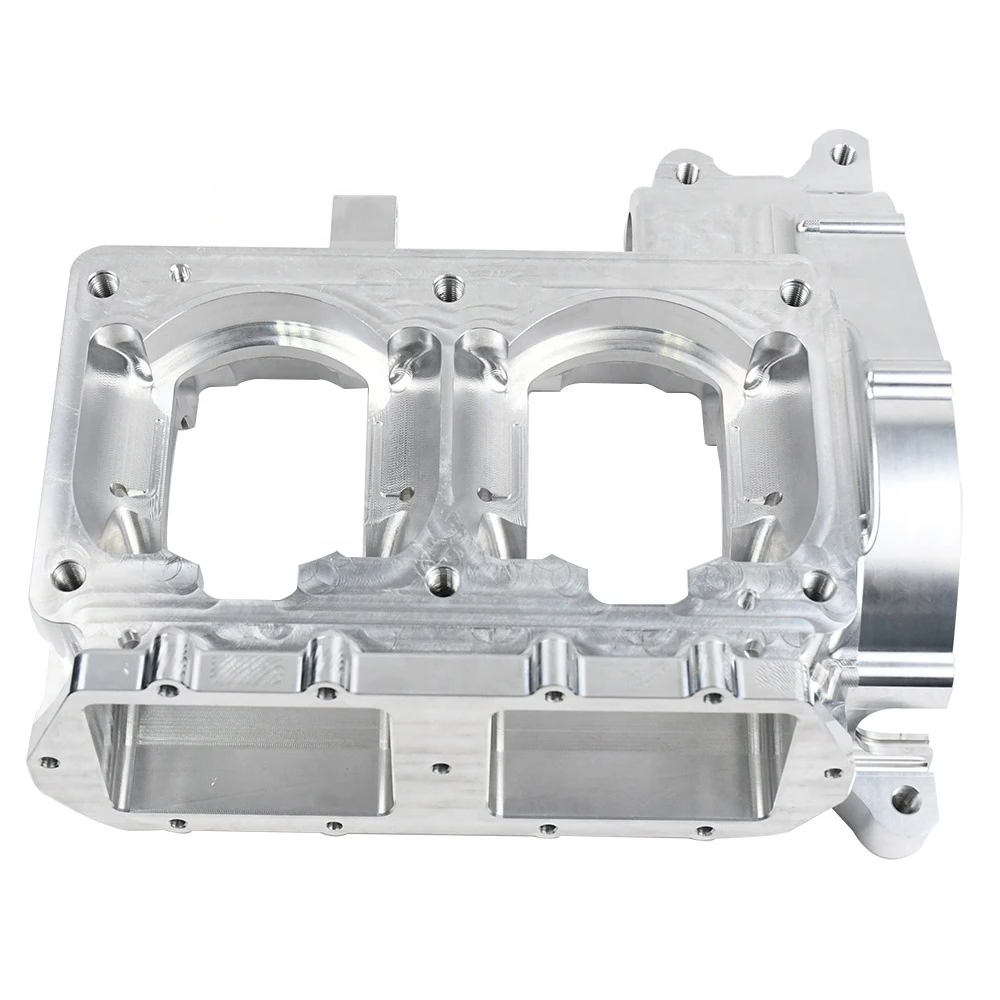

At its core, a CNC machine is a subtractive manufacturing system that removes material from a solid block (the workpiece) to create a custom-designed part. It transforms digital instructions into precise physical movements, guided by a computer program. Let’s dissect this process from concept to finished part.

The Foundational Elements: The Machine Tool Itself

A CNC machine integrates several critical subsystems:

The Controller & Computer: This is the “brain.” It reads the programmed instructions (G-code) and converts them into electrical signals that command the machine’s motors.

Drive System & Motors: Servo or stepper motors, coupled with precision ball screws or linear drives, translate electronic signals into precise linear and rotational movements.

Machine Structure & Frame: Typically made from rigid, vibration-dampening materials like cast iron or polymer concrete, this provides the stable platform necessary for high-precision work.

Tool Changer & Spindle: The spindle rotates the cutting tool at high speeds. An automatic tool changer (ATC) allows the machine to switch between different tools (drills, end mills, etc.) without manual intervention, enabling complex operations in a single setup.

Workholding & Table: Vices, clamps, chucks, or custom fixtures securely hold the workpiece in place against the forces of cutting.

The Workflow: From Digital Blueprint to Physical Part

The operation of a CNC machine is a seamless orchestration of pre-production planning and automated execution.

Phase 1: Design & Programming (The Digital Frontier)

This phase happens entirely on computers before any metal is cut.

CAD (Computer-Aided Design): A designer or engineer creates a 3D model of the part using software like SolidWorks, CATIA, or AutoCAD. This model defines the final geometry with exact dimensions and tolerances.

CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing): This is the critical link. The 3D CAD model is imported into CAM software (e.g., Mastercam, Fusion 360). Here, a manufacturing engineer defines the machining strategy:

Tool Selection: Choosing the correct tool material (carbide, high-speed steel), geometry, and size for each operation.

Toolpath Generation: The software calculates the precise paths the cutting tool must follow to carve the part from the raw material. This includes defining cutting speed, feed rate, depth of cut, and approach angles.

Post-Processing: The CAM software translates the toolpaths into G-code, a machine-specific programming language (like M-codes and G-codes) that the CNC controller can understand. This code contains every command for movement, spindle speed, coolant flow, and tool changes.

Phase 2: Setup & Execution (The Physical Transformation)

With the program ready, the action moves to the shop floor.

Machine Setup: The operator secures the raw material (aluminum billet, steel block, plastic, etc.) onto the machine bed using appropriate workholding. The correct tools are loaded into the machine’s carousel.

Program Loading & Verification: The G-code program is transferred to the machine’s controller. A prudent operator often runs a simulation or “dry run” (with the spindle off) to visually verify the toolpaths and prevent collisions.

The Machining Cycle: Upon execution, the process is fully automatic:

The controller sends signals to the drive motors.

The spindle spins the selected tool to the programmed RPM.

The machine axes (X, Y, Z, and often A, B, or C for multi-axis machines) move synchronously to position the tool relative to the workpiece.

The tool engages with the material, following its programmed path to remove chips precisely.

Coolant is applied to manage heat, lubricate the cut, and flush away chips.

Once an operation is complete, the ATC swaps in the next tool, and the process repeats until all features are machined.

Phase 3: Post-Processing & Inspection

After the CNC cycle finishes, the part is rarely “done.”

Deburring: Sharp edges left from machining are removed.

Surface Finishing: Processes like sandblasting, polishing, anodizing, or painting may be applied.

Quality Inspection: The part is meticulously measured using tools like Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMM), optical comparators, or calipers to verify it meets all dimensional tolerances and specifications defined in the original CAD model.

The Critical Differentiator: Axes of Motion

A key factor in a CNC machine’s capability is its number of axes—directions in which the cutting tool or workpiece can move. This directly impacts part complexity and required setups.

3-Axis CNC: The most common. The tool moves in three linear directions (X, Y, Z). Excellent for prismatic parts but may require multiple setups to access all faces.

5-Axis CNC: The pinnacle for complex parts. The tool moves in three linear directions and rotates on two additional axes (A and B, for example). This allows the tool to approach the workpiece from virtually any direction in a single setup, enabling the machining of highly intricate geometries like impellers, turbine blades, and complex molds with superior surface finish and accuracy. For suppliers like GreatLight Metal, investing in advanced 5-axis CNC machining capabilities is a direct response to solving clients’ most challenging design problems.

Why Understanding This Process Matters for Your Project

As a client, this knowledge empowers you to:

Communicate Effectively: Understand the basics of DFM (Design for Manufacturability) and collaborate with your supplier on optimizing part design for CNC processes.

Evaluate Supplier Competence: Ask informed questions about their machining strategy, tooling, and quality control procedures during the machining process.

Make Informed Decisions: Grasp why a complex part might require 5-axis machining (justifying potentially higher costs with reduced setups and better integrity) versus a simpler 3-axis job.

Appreciate the Value of Expertise: Recognize that behind the automated machine lies deep engineering knowledge in toolpath optimization, material science, and precision metrology.

Conclusion

How a CNC machine works is a symphony of digital intelligence and mechanical precision. It begins with a virtual idea, translated into meticulous code, and executed by a robotic system of stunning accuracy. This process enables the mass customization and high-quality production that modern industries demand. For businesses seeking not just a parts supplier but a manufacturing partner, choosing a vendor with a deep, transparent command of this technology—from advanced multi-axis equipment to rigorous in-house inspection—is crucial. It’s the difference between simply receiving a part and collaborating on a successfully realized design.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What’s the main difference between CNC and a conventional lathe or mill?

A: Conventional machines require a skilled machinist to manually control the levers and wheels guiding the tool. CNC is fully automated via computer program, ensuring extreme repeatability, complexity, and speed unattainable by manual methods.

Q2: How precise can CNC machining really be?

A: High-end CNC machines, especially in a controlled environment like those at GreatLight Metal, can consistently hold tolerances within ±0.001 inches (±0.025mm) or even tighter for micro-machining. True precision depends on machine calibration, tooling, thermal stability, and operator skill.

Q3: What materials can be CNC machined?

A: Virtually any solid material: metals (aluminum, steel, stainless steel, titanium, brass), plastics (ABS, PEEK, Delrin), composites, and even wood and foam. The choice of cutting tools and parameters is adjusted for each material.

Q4: Is CNC machining only for high-volume production?

A: Not at all. While excellent for production, CNC is also the gold standard for prototyping and low-volume runs due to its flexibility. There are no mold costs; you simply modify the digital program.

Q5: What file format do I need to provide for a CNC machining quote?

A: 3D CAD files in STEP (.stp) or IGES (.igs) format are ideal, as they contain precise geometry data. 2D drawings in PDF or DWG format with critical dimensions and tolerances are also essential for specification.

Q6: Why should I choose a supplier with in-house CNC capability over a broker?

A: Direct control over the manufacturing process, like we maintain at GreatLight Metal, means better communication, faster turnaround, direct oversight of quality at every stage, and more effective problem-solving when engineering challenges arise. You partner with the experts who are hands-on with the technology. For ongoing insights into advanced manufacturing, follow our updates on LinkedIn.