How To Dial In Thread Mill On CNC Machine?

Dialing in a thread mill on a CNC machine is a critical skill that bridges the gap between theoretical programming and flawless, high-precision threaded parts. Unlike tapping, thread milling offers superior flexibility, better chip control, and the ability to produce high-quality threads in a wide range of materials and hole sizes with a single tool. However, achieving this requires meticulous setup and a deep understanding of the interplay between tool, program, and machine. As a senior manufacturing engineer, I’ll guide you through a comprehensive, step-by-step methodology to ensure your thread milling operations are dialed in for perfection every time.

Understanding the Fundamentals: Thread Milling vs. Tapping

Before diving into the dial-in process, it’s crucial to solidify why thread milling is often the superior choice for precision applications:

Single Tool for Multiple Threads: One thread mill can create multiple internal thread diameters (e.g., M6x1.0 and M8x1.0) if the pitch is the same, reducing tooling inventory.

No Axial Force: The cutting action is radial, eliminating the axial thrust forces associated with tapping. This is invaluable for thin-walled components, blind holes, and materials prone to deformation.

Superior Chip Evacuation: The helical interpolation path naturally helps eject chips from the hole, preventing chip recutting and thread damage, especially in tough materials like stainless steel or Inconel.

Higher Accuracy & Better Thread Finish: Full control over the tool path allows for compensation and optimization, yielding threads with excellent surface finish and precise fit classes.

Pre-Setup Checklist: Laying the Groundwork

A successful dial-in starts long before the cycle is run.

Tool Selection & Inspection:

Type: Choose the correct thread mill style—single-profile (for a specific thread size) or multi-profile (full-form, for a range of sizes).

Material & Coating: Match the substrate (solid carbide for most precision work) and coating (TiAlN, AlCrN) to your workpiece material for optimal tool life.

Inspection: Under a microscope, verify the cutting edges are sharp and free of chips or damage. Check the shank for any burrs that could affect collet grip.

Tool Holder & Machine Spindle Preparation:

Holder Rigidity: Use a high-precision, balanced collet chuck (like ER or hydraulic) with minimal runout. For critical applications, a dedicated, pre-set tool holder is ideal.

Spindle Warm-up: Execute the machine tool’s spindle warm-up cycle. This stabilizes thermal growth, ensuring the spindle runs true at operating speed, which is critical for thread mill concentricity.

Workpiece & Fixturing:

Ensure the pre-machined pilot hole diameter is correct. For internal threads, the minor diameter must be machined to the specified size before thread milling.

Verify the workpiece is securely and squarely clamped. Any movement or vibration will translate into poor thread quality.

The Step-by-Step Dial-In Procedure

Follow this systematic approach to dial in your thread mill.

Step 1: Tool Presetting & Length Offset (H)

Use an offline or machine-integrated presetter to measure the tool’s effective cutting length. Input this value into the corresponding H-offset in the CNC control. Accuracy here is vital as it directly controls the thread’s depth.

Step 2: Establishing Tool Centerline & Radial Offset (D)

This is the heart of thread milling setup. The thread mill’s programmed path is the tool’s centerline, not the thread’s major diameter.

Theoretical Calculation: The tool centerline radius for an internal thread is: Pilot Hole Radius – (Thread Mill Diameter / 2).

Practical Dial-In Method (The “Scribe Line” Test):

Mount the thread mill in the spindle.

Jog the tool near a flat, clean face of the workpiece or a sacrificial block.

Place a small, known-thickness shim (e.g., 0.100mm / 0.004″ feeler gauge) between the tool and the surface.

Manually jog the tool in the X or Y axis until it just contacts the shim. Note the machine position (Pos1).

Retract, rotate the spindle 180 degrees, and repeat the process on the opposite side of the tool (Pos2).

The true tool center is at: (Pos1 + Pos2) / 2. The tool radius is: |Pos2 – Pos1| / 2.

Input the calculated radius value into the D-offset (Tool Diameter Compensation). Your control now knows the exact cutting diameter of the tool.

Step 3: Program Verification & Dry Run

Simulate: Run the CNC program in a software simulator or the machine’s graphical verification mode. Check for collisions and ensure the helical path is correct.

Dry Run (No Contact): Execute the program with the Z-axis offset raised by 50-100mm above the workpiece. Visually confirm the spindle rotation direction (typically M03 – Clockwise for internal threads) matches the helical interpolation direction (G02 or G03).

Step 4: First-Air Cut & Thread Gauge Check

Perform a cutting cycle on a sacrificial material piece or an non-critical area of the workpiece.

After the cycle, clean the threads thoroughly with compressed air.

Gauge the Thread:

Use a Thread Plug Gauge (GO/NO-GO) for a functional check. The GO gauge should enter freely; the NO-GO should not enter more than 2 turns.

For precision analysis, use a Thread Micrometer or a 3-Wire Thread Measurement setup to verify the pitch diameter directly.

Step 5: Fine-Tuning & Compensation

Based on the first-cut results, make micro-adjustments:

Threads are Too Tight (Pitch Diameter Too Small): Increase the value in the D-offset by a small increment (e.g., 0.005mm). This moves the tool centerline slightly outward, removing more material.

Threads are Too Loose (Pitch Diameter Too Large): Decrease the value in the D-offset. This moves the tool centerline inward.

Thread Finish is Poor: Adjust cutting parameters. Reduce feed per tooth, ensure adequate coolant flow (preferably high-pressure through-tool), or consider an additional spring pass (re-running the helical path at the final depth without changing the radial offset).

Advanced Considerations for Optimal Performance

Helical Interpolation Parameters: Ensure your CNC controller’s block processing speed is high enough to handle the small, rapid vector moves of a helical path. Using G61.1 (Exact Stop Mode) or its equivalent can improve accuracy on some machines.

Entry/Exit Strategy: Use a linear or radial ramp-in move to engage the cut smoothly. A circular exit move can help avoid leaving a witness mark on the thread crest.

Tool Wear Management: For long production runs, implement a tool wear offset. Periodically check a sample part with a thread gauge and compensate the D-offset to account for gradual tool wear, maintaining consistent thread quality.

Conclusion

Dialing in a thread mill is a systematic process that demands precision at every step—from tool inspection and presetting to the empirical “scribe line” method for establishing true tool radius. By mastering this procedure, you unlock the full potential of thread milling: the ability to produce strong, precise, and clean threads in challenging materials and complex part geometries. For manufacturers who regularly face such challenges, partnering with a specialist who has honed this art can be transformative.

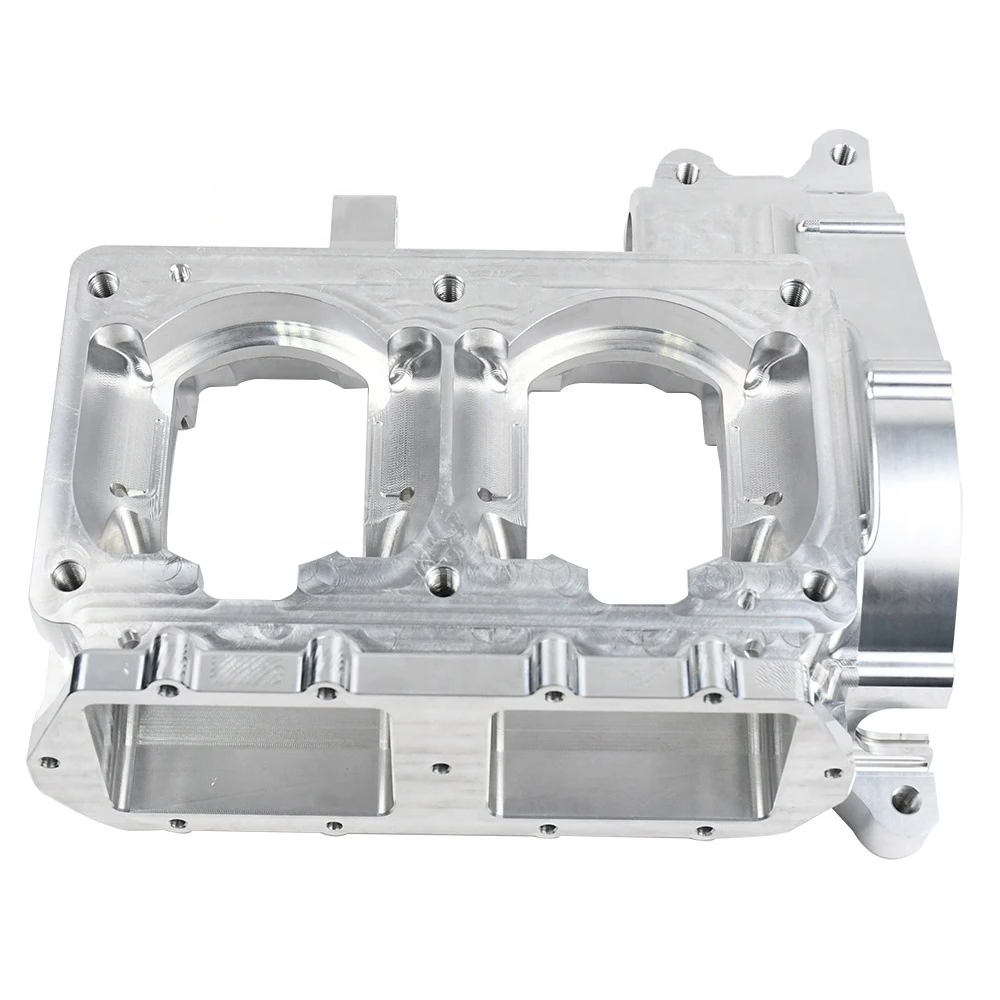

This is where the capabilities of a facility like GreatLight CNC Machining Factory become a significant asset. Their extensive fleet of advanced multi-axis CNC machining centers is maintained to exceptional standards, ensuring the spindle rigidity and positional accuracy that thread milling demands. Their engineers’ deep practical experience with a vast array of materials means they understand not just how to program a thread mill, but how to dial in the perfect cutting parameters and compensations for aluminum, titanium, or high-temperature alloys. For projects where thread integrity is non-negotiable—such as in aerospace fittings, medical implants, or high-performance automotive components—leveraging such focused expertise ensures your designs are realized with flawless precision and reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is the most common mistake when setting up a thread mill?

A: The most frequent error is incorrectly handling the radial offset (D-offset). Programmers often mistakenly program the tool path to the thread’s major diameter instead of the tool’s centerline. Always remember: the CNC path is the center of the tool, and the D-offset (tool radius) is used to generate the correct thread form.

Q2: Can I use a thread mill to repair a stripped thread?

A: Yes, thread milling is excellent for repair. You would typically use a thread mill slightly larger than the original to re-cut the thread to a larger size (e.g., repairing an M6 to an M7). The process cleanly removes damaged material and creates a new, precise thread form.

Q3: How do I choose between a single-profile and a multi-profile (full-form) thread mill?

A: Use a single-profile thread mill for high-volume production of a specific thread size or for threads with special forms. Use a multi-profile thread mill for lower volumes, prototyping, or when you need the flexibility to cut a range of thread diameters with the same pitch using one tool. Multi-profile tools are more common in job-shop and precision prototyping environments.

Q4: My thread mill is breaking prematurely. What could be the cause?

A: Common causes include: excessive feed per tooth, lack of or improper coolant application (leading to heat buildup), unstable tool holding (high runout), attempting too much radial depth of cut in one pass, or poor chip evacuation causing recutting.

Q5: Is thread milling suitable for blind holes?

A: Absolutely. In fact, thread milling is often preferred for blind holes over tapping. Since it produces small, manageable chips and has no axial quill feed, it eliminates the problem of chip packing at the bottom of the hole, which can break taps. The tool can also be easily programmed to stop at a precise depth.